| World Journal of Oncology, ISSN 1920-4531 print, 1920-454X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, World J Oncol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.wjon.org |

Original Article

Volume 2, Number 5, October 2011, pages 225-231

Comorbid Conditions in Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

Alex Z Fua, d, Zhongyun Zhaob, Sue Gaob, Beth Barberb, Gordon G Liuc

aDepartment of Quantitative Health Sciences, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA

bAmgen Inc, One Amgen Center Drive, Thousand Oaks, CA 91320-1799, USA

cGuanghua School of Management, Peking University, Beijing, China

dCorresponding author: Alex Z Fu, Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Cleveland Clinic, 9500 Euclid Avenue/JJN3-01 Cleveland, OH 44195 USA

Manuscript accepted for publication September 23, 2011

Short title: Comorbid Conditions in Metastatic CRC

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/wjon370e

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) often have other medical conditions that may impact treatment decisions, prognoses and quality of care. We aimed to assess co-existing medical conditions in the mCRC patient population. This retrospective cohort study used linked medical and pharmacy claims data from two US-based Medstat MarketScan claims databases and identified patients with newly diagnosed mCRC between January 2005 and June 2008.

Methods: Patient data were analyzed for comorbid conditions and medication use in the year prior to diagnosis of mCRC. Univariate analyses were conducted to compare the comorbid conditions between patients aged ≥ 65 and < 65 years old. In total, 12 648 patients aged ≥ 18 years were identified. The study was evenly populated by gender and age above and below 65, and most patients had a primary diagnosis of colon cancer (70.1%).

Results: The most prevalent comorbidity was cardiovascular disease (CVD) (55.7% of patients) including hypertension (40.8%), cardiac dysrhythmia (14.2%), coronary artery disease (13.5%), congestive heart failure (7.2%) and arterial and venous thromboembolism (6.2% and 4.6%, respectively). Most comorbidities were significantly more prevalent in patients ≥ 65 years of age, particularly with respect to CVD (67.9% versus 42.5%, respectively; P < 0.0001). Additionally, nearly half (49.7%) of the patients received antihypertensive agents and many patients were prescribed more than one class of medications prior to mCRC diagnosis.

Conclusions: Comorbid medical conditions, particularly CVDs, are common in patients with mCRC, which could increase the complexity of patient management. This should be a consideration integral to the selection of the most appropriate treatment for individual patients.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease; Comorbidities; Metastatic colorectal cancer; Patient management

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of death from cancer in the USA, with 146 970 new cases and 49 920 deaths estimated in 2008 [1]. Of newly diagnosed CRC patients, 15% to 25% have metastatic disease at diagnosis, while disease recurrence and the development of distant metastases occur in up to 50% of all patients initially diagnosed at earlier disease stages [2]. Similarly in Europe, CRC is also the second most common form of cancer and the second most common cause of death from cancer [3].

Overall survival for patients with metastatic CRC (mCRC) has increased dramatically in the last 20 years largely due to advances in systemic therapy (newer chemotherapies and the introduction of biologic agents) [4]. Additionally, the treatment has become more personalized for patients with mCRC. For example, the benefits of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antagonists cetuximab and panitumumab are limited to patients with wild-type KRAS (the proto-oncogene Kirsten ras sarcoma virus) mCRC. Although there are significant gains in clinical benefit, biologics are associated with recognized adverse events (AEs) that may limit their beneficial effects in some patients [5-7]. Gastrointestinal perforations, fistulae, haemorrhage, hypertension and arterial thromboembolism are some of the serious AEs associated with bevacizumab [8, 9], while the EGFR antagonist class is associated with hypomagnesaemia, infusion reactions and skin toxicities [7, 10-14].

The incorporation of the three different biologic treatments into the mCRC armamentarium offers a degree of flexibility regarding the most appropriate choice of biologics. Consideration of AE risk plays a role in treatment selection to ensure an acceptable risk–benefit profile. Pre-existing comorbidities in patients with mCRC may also play a role in order to avoid toxicity issues [15]. Taking age and comorbidities into consideration as part of treatment selection is, therefore, not uncommon in the management of cancer. For example, in advanced lung cancer, both age and comorbidity play an important role in treatment decisions [16]. There are, however, limited existing data regarding the extent of comorbid conditions in patients with mCRC.

The aim of this study was to comprehensively assess co-existing medical conditions in the mCRC patient population in clinical practice.

| Methods | ▴Top |

Source data

This was a retrospective cohort study using longitudinal, integrated medical and pharmacy claims data from two Medstat MarketScan claims databases: the Commercial Claims and Encounters database and the Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits database. These databases include fully de-identified patient-level, paid and adjudicated medical and pharmacy claims histories of 30 million covered lives belonging to 12 national and regional health plans in the USA. The databases are representative of the US national commercially-insured population and those who have both Medicare coverage and supplemental employer-sponsored coverage. They capture the full continuum of care in all settings including physician office visits, hospital stays and outpatient pharmacy claims.

Sample selection and data extraction

Data on patients with newly diagnosed mCRC between January 2005 and June 2008 were extracted from the databases using the International Classification of Disease 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes for CRC (153.x [excluding 153.5], 154.0, 154.1, 154.8) and distant metastasis (196.0, 196.1, 196.3, 196.5, 197.x [excluding 197.5], 198, 199.0). The index date was defined as the date of the initial mCRC diagnosis. Only patients aged ≥18 years at the index date and with at least 1-year continuous medical and drug benefit coverage prior to the index date, and with a first identified distant metastasis diagnosis date no more than 30 days after the first identified CRC diagnosis date were included in the data set. Demographic and clinical characteristics reported included age, gender, geographical location, type of insurance plan, cancer type (colon versus rectal) and location of metastases.

Comprehensive comorbidities were examined in this study including cardiovascular disease (CVD); existing wounds (bone fractures, wound-healing complications, open wounds); history of bleeding/haemorrhage; digestive system disorders; diabetes mellitus; diseases of the blood; diseases of the skin; respiratory system disorders; smoking history; renal failure; and obesity. Using ICD-9 diagnosis codes, comorbid medical conditions were examined during the 1-year prior to the index date, and in the case of traumatic conditions (e.g., bone fracture and open wound) data during 30 days prior to the index date were assessed. Additionally, data on medications taken during the 1 year prior to the index date were extracted using prescription information.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographics and comorbid conditions defined by ICD-9 codes prior to mCRC diagnosis were summarized descriptively for the overall patient population using the 1-year pre-index period data. Similarly, medications received prior to mCRC diagnosis were summarized descriptively. Univariate analyses were conducted to compare the comorbid conditions between patients aged ≥ 65 and < 65 years old. Chi-square tests were used to compare proportions of comorbidities between patients aged ≥ 65 and < 65 years old.

| Results | ▴Top |

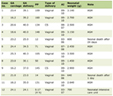

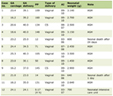

Based on the selection criteria, 12 648 patients were eligible for inclusion in the analysis of comorbid conditions and medication use in the year prior to diagnosis of mCRC. The study population had 54% of men, and just over half were aged > 65 years (52%). The majority of the study population had a primary diagnosis of colon cancer (70%) as opposed to rectal cancer, and the mean age of the study population (standard deviation) was 66.3 (13.1) years (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Characteristics of Study Population |

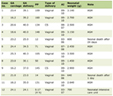

The most frequent comorbidities in the overall population are shown in Table 2, which indicates that CVDs were most commonly reported (55.7%), followed by digestive system disorders (29%), a history of bleeding (28.3%) and diabetes mellitus (19.1%). Among the patients with comorbid CVD, hypertension was the most common condition (40.8%) followed by heart disease (28%), including cardiac dysrhythmia (14.2%), coronary artery disease (13.5%), congestive heart failure (7.2%), ischemic heart disease (6.2%), arterial thromboembolism (ATE) (6.2%), and venous thromboembolism (VTE) (4.6%).

Click to view | Table 2. Comorbid conditions: numbers and percentages (N = 12 648) |

Elderly patients ≥ 65 years of age had a significantly higher prevalence of CVDs compared with younger patients (67.9% versus 42.5% respectively; P < 0.0001; Table 2). Similarly, individual heart-related comorbidities were significantly more prevalent in those aged ≥ 65 years (39.5% versus 15.6%; P < 0.0001) with the exception of acute myocarditis (Table 2). The prevalence of diabetes mellitus was also significantly higher among the older age group (21.6% versus 16.5%; P < 0.0001), as were comorbidities relating to diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, renal failure and insufficiency, and respiratory diseases (P < 0.0001). Obesity and history of bleeding were the only two comorbidities with a significantly higher prevalence in those aged < 65 years of age (P < 0.0001).

Medications received prior to diagnosis are shown in Table 3. The most common medications were antibiotics (61.7%), and antihypertensive agents (49.7%). The percentages in Table 3 cumulatively suggest that many patients were prescribed more than one class of medications prior to mCRC diagnosis.

Click to view | Table 3. Medications Received Prior to Diagnosis of mCRC (N = 12 648) |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The findings of this retrospective cohort study indicate that comorbid medical conditions are common in patients with mCRC. CVDs are the most prevalent comorbidities, and are significantly more prevalent in patients over 65 years old, affecting more than two-thirds of this group. As might be anticipated based on the comorbidities identified, this study also showed that patients with mCRC are frequently treated with non-CRC-related medications, mostly for CVDs and gastrointestinal diseases. The high frequency of CVD as a comorbidity in this study population might be anticipated given that more than half of patients were > 65 years of age. In addition to hypertension, the most frequently reported CVDs were heart diseases (including cardiac dysrhythmia and congestive heart failure), stroke, ATE and VTE.

Although data on pre-existing comorbidities in mCRC are limited, some information is available on patients with CRC of any stage in whom the most common comorbidities are reported to be similar to those presented here. Yancik et al [17] reported hypertension, serious heart conditions, gastrointestinal problems, arthritis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as the most prominent comorbid conditions in patients with colon cancer of any stage and these findings have been corroborated by later studies [18-20]. Our finding showed that many co-existing conditions, including the majority of CVD comorbidities, diabetes mellitus, diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, renal failure and insufficiency, and respiratory diseases, occurred more frequently in patients aged > 65 years is also supported by data from the colon cancer setting [17].

Some of the comorbidities identified in our study are likely to be of particular importance to consider. For example, comorbid conditions relating to a history of bleeding and/or existing wounds were identified in 28.3% and 15.9% of patients in this cohort study, respectively. Wound-healing complications have also been linked with treatment regimens that include bevacizumab [8, 21]. This may be particularly important in patients who are eligible for metastasectomy. In consideration of these factors, a delay in elective surgery of up to 8 weeks after completion of bevacizumab, and a similar delay in restarting after liver surgery, is recommended [22].

Our findings also show that VTE and ATE occurred in 4.6% and 6.2% of patients with mCRC, respectively. A recent meta-analysis evaluating the use of bevacizumab in nearly 8000 patients with a variety of advanced solid tumours from 15 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) concluded that the drug was significantly associated with an increased risk of developing VTE (P < 0.001) compared with controls, an effect independent of dose [23]. An earlier meta-analysis found an association between bevacizumab and ATE (P = 0.031) using data from five RCTs [24].

Comorbid diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue together were identified in 4.7% of all patients, increasing in frequency in the elderly sub-population. This is of relevance to the management of mCRC as skin toxicities are frequently reported in clinical trials of cetuximab and panitumumab [7, 11, 14, 25].

Our study is associated with a number of limitations. The comorbidities identified in this study were based on healthcare service use data, thus comorbid conditions that did not trigger healthcare service use in the year prior to mCRC diagnosis were not captured. Also, the prevalence rates for conditions of smoking history and obesity identified in this study were very low. This is likely due to under-reporting of these two conditions in claims databases. Finally, our results are reflective of the population studied and may not be extrapolated to the mCRC population in general.

In conclusion, comorbid conditions were frequently observed in patients prior to a diagnosis of mCRC. The presence of these comorbidities increases the complexity of managing the patient’s condition. In current treatment guidelines, the presence of comorbidities is included as a factor that should be considered in the choice of chemotherapy for mCRC [15]. Given that, in addition to chemotherapy, there is now a choice of biologic agents for mCRC, each with a well-defined and distinct AE profile, consideration of comorbid conditions should now be integral to the selection of all components of the treatment regimen for individual patients with mCRC.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Amgen Inc. Medical writing assistance was provided by ApotheCom ScopeMedical Ltd, funded by Amgen Inc. Alex Z Fu and Gordon G Liu received funding from Amgen Inc to perform the analyses reported in this manuscript. Zhongyun Zhao, Sue Gao and Beth Barber are employees of Amgen Inc.

| References | ▴Top |

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(4):225-249.

pubmed doi - Kindler HL, Shulman KL. Metastatic colorectal cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2001;2(6):459-471.

pubmed doi - Ferlay J, Autier P, Boniol M, Heanue M, Colombet M, Boyle P. Estimates of the cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2006. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(3):581-592.

pubmed doi - Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, Eng C, Sargent DJ, Larson DW, Grothey A,

et al . Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(22):3677-3683.

pubmed doi - Giantonio BJ, Catalano PJ, Meropol NJ, O'Dwyer PJ, Mitchell EP, Alberts SR, Schwartz MA,

et al . Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFOX4) for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: results from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E3200. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(12):1539-1544.

pubmed doi - Jonker DJ, O'Callaghan CJ, Karapetis CS, Zalcberg JR, Tu D, Au HJ, Berry SR,

et al . Cetuximab for the treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(20):2040-2048.

pubmed doi - Van Cutsem E, Peeters M, Siena S, Humblet Y, Hendlisz A, Neyns B, Canon JL,

et al . Open-label phase III trial of panitumumab plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care alone in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(13):1658-1664.

pubmed doi - Roche. Avastin® US prescribing information. 2010.

- Saltz LB, Clarke S, Diaz-Rubio E, Scheithauer W, Figer A, Wong R, Koski S,

et al . Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(12):2013-2019.

pubmed doi - ImClone Systems Inc. and Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. Erbitux® US prescribing information. 2010.

- Van Cutsem E, Kohne CH, Hitre E, Zaluski J, Chang Chien CR, Makhson A, D'Haens G,

et al . Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1408-1417.

pubmed doi - Amgen Inc. Vectibix® US prescribing information. 2010.

- Peeters M, Price TJ, Cervantes A, Sobrero AF, Ducreux M, Hotko Y, Andre T,

et al . Randomized phase III study of panitumumab with fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) compared with FOLFIRI alone as second-line treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(31):4706-4713.

pubmed doi - Douillard JY, Siena S, Cassidy J, Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, Humblet Y,

et al . Randomized, phase III trial of panitumumab with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4) versus FOLFOX4 alone as first-line treatment in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: the PRIME study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(31):4697-4705.

pubmed doi - National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Colon Cancer, 2010a (V.3.2010) [http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/colon.pdf]. Last accessed August 2010.

- Blanco JA, Toste IS, Alvarez RF, Cuadrado GR, Gonzalvez AM, Martin IJ. Age, comorbidity, treatment decision and prognosis in lung cancer. Age Ageing. 2008;37(6):715-718.

pubmed doi - Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA, Havlik RJ, Long S, Edwards BK, Yates JW. Comorbidity and age as predictors of risk for early mortality of male and female colon carcinoma patients: a population-based study. Cancer. 1998;82(11):2123-2134.

pubmed doi - Gross CP, Guo Z, McAvay GJ, Allore HG, Young M, Tinetti ME. Multimorbidity and survival in older persons with colorectal cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(12):1898-1904.

pubmed doi - Janssen-Heijnen ML, Maas HA, Houterman S, Lemmens VE, Rutten HJ, Coebergh JW. Comorbidity in older surgical cancer patients: influence on patient care and outcome. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(15):2179-2193.

pubmed doi - Shack LG, Rachet B, Williams EM, Northover JM, Coleman MP. Does the timing of comorbidity affect colorectal cancer survival? A population based study. Postgrad Med J. 2010;86(1012):73-78.

pubmed doi - Hochster HS, Hart LL, Ramanathan RK, Childs BH, Hainsworth JD, Cohn AL, Wong L,

et al . Safety and efficacy of oxaliplatin and fluoropyrimidine regimens with or without bevacizumab as first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: results of the TREE Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(21):3523-3529.

pubmed doi - Ellis LM, Curley SA, Grothey A. Surgical resection after downsizing of colorectal liver metastasis in the era of bevacizumab. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):4853-4855.

pubmed doi - Nalluri SR, Chu D, Keresztes R, Zhu X, Wu S. Risk of venous thromboembolism with the angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(19):2277-2285.

pubmed doi - Scappaticci FA, Skillings JR, Holden SN, Gerber HP, Miller K, Kabbinavar F, Bergsland E,

et al . Arterial thromboembolic events in patients with metastatic carcinoma treated with chemotherapy and bevacizumab. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(16):1232-1239.

pubmed doi - Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A, Hartmann JT, Aparicio J, de Braud F, Donea S,

et al . Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(5):663-671.

pubmed doi

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

World Journal of Oncology is published by Elmer Press Inc.