| World Journal of Oncology, ISSN 1920-4531 print, 1920-454X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, World J Oncol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.wjon.org |

Original Article

Volume 11, Number 4, August 2020, pages 173-181

Oral and Oropharyngeal Cancers and Possible Risk Factors Across Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: A Systematic Review

Wedad Saeed Alqahtania, Nawaf Abdulrahman Almufarehb, Halah A. Al-Johanic, Rasil Khaled Alotaibid, Consul Iworikumo Julianae, Nada Hamad Aljarbaf, Abdulqader Saeed Alqahtanig, Bandary Almarshedyh, Abdelbaset Mohamed Elasbalii, Hussain Gadelkarim Ahmedj, k, l, Bassam Ahmed Almutlaqj

aFaculty of Biology, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Saudi Arabia

bDepartment of Paediatric Dentistry and Preventive Dental Sciences, Riyadh Elm University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

cDepartment of Biology, Faculty of Science, Taibah University, Madina, Saudi Arabia

dCollege of Dentistry, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

eNiger Delta University, Bayelsa State, Niger

fDepartment of Biology, College of Science. Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

gRoyal Commission Hospital, Pharmacy Department, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

hMinistry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

iDepartment of Clinical Laboratory Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Jouf University, Qurayyat, Saudi Arabia

jCollege of Medicine, University of Hail, Saudi Arabia

kDepartment of Histopathology and Cytology, FMLS, University of Khartoum, Sudan

lCorresponding Author: Hussain Gadelkarim Ahmed, College of Medicine, University of Hail 2440, Saudi Arabia

Manuscript submitted April 11, 2020, accepted May 15, 2020, published online August 10, 2020

Short title: O-OPCs in GCC Countries

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/wjon1283

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: In recent years, there is an emerging increase in the prevalence of oral and oropharyngeal cancers (O-OPCs) across the Arabian Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Consequently, this review aimed to explore the epidemiology and possible risk factors of O-OPCs in GCC countries.

Methods: Data published after 2008 related to O-OPCs in GCC countries were obtained through electronic searches in Medline/PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE and Google Scholar. Keywords related to the association between O-OPCs metrics (epidemiology and risk factors) and GCC countries were used for electronic searches.

Results: The overall prevalence of OPCs increased significantly over time (40-51%) in some countries (Saudi Arabia and Arab Emigrated) of the Gulf regions. The pooled risk factor was 3.4 (2.5 - 4.7). Among the risk factors, human papillomavirus and the use of smoke and smokeless tobacco revealed odds ratio (OR) 3.31 (3.13 - 4.5) and 0.60 (0.45 - 0.80) at 95% confidence interval (CI).

Conclusion: A positive correlation between factors like age, diet, hygiene, genetics, viral and bacterial infection, consumption of alcohol and tobacco products with OPC-MFC is suggested.

Keywords: Oral cancer; GCC countries; Oropharyngeal cancer; HPV; Tobacco

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Oral and oropharyngeal cancers (O-OPCs) group represents the sixth most common cancer with around 500,000 cases worldwide [1]. There is an alarming increasing incidence of O-OPCs in younger patients particularly in the Middle East (14.5%) and Africa (17.2%) [2]. A major variation in the epidemiology of O-OPCs was observed based on geographical distribution, sex and age worldwide [3]. Numerous risk factors have been implicated in the etiology of O-OPCs including tobacco use, alcohol consumption, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, poor oral hygiene, low socioeconomic status and genetic factors [4, 5], and factors such as ethnic groups, lifestyle, occupational exposure, immune deficits, familial risk and lack of fruits/vegetable regular eating [6, 7].

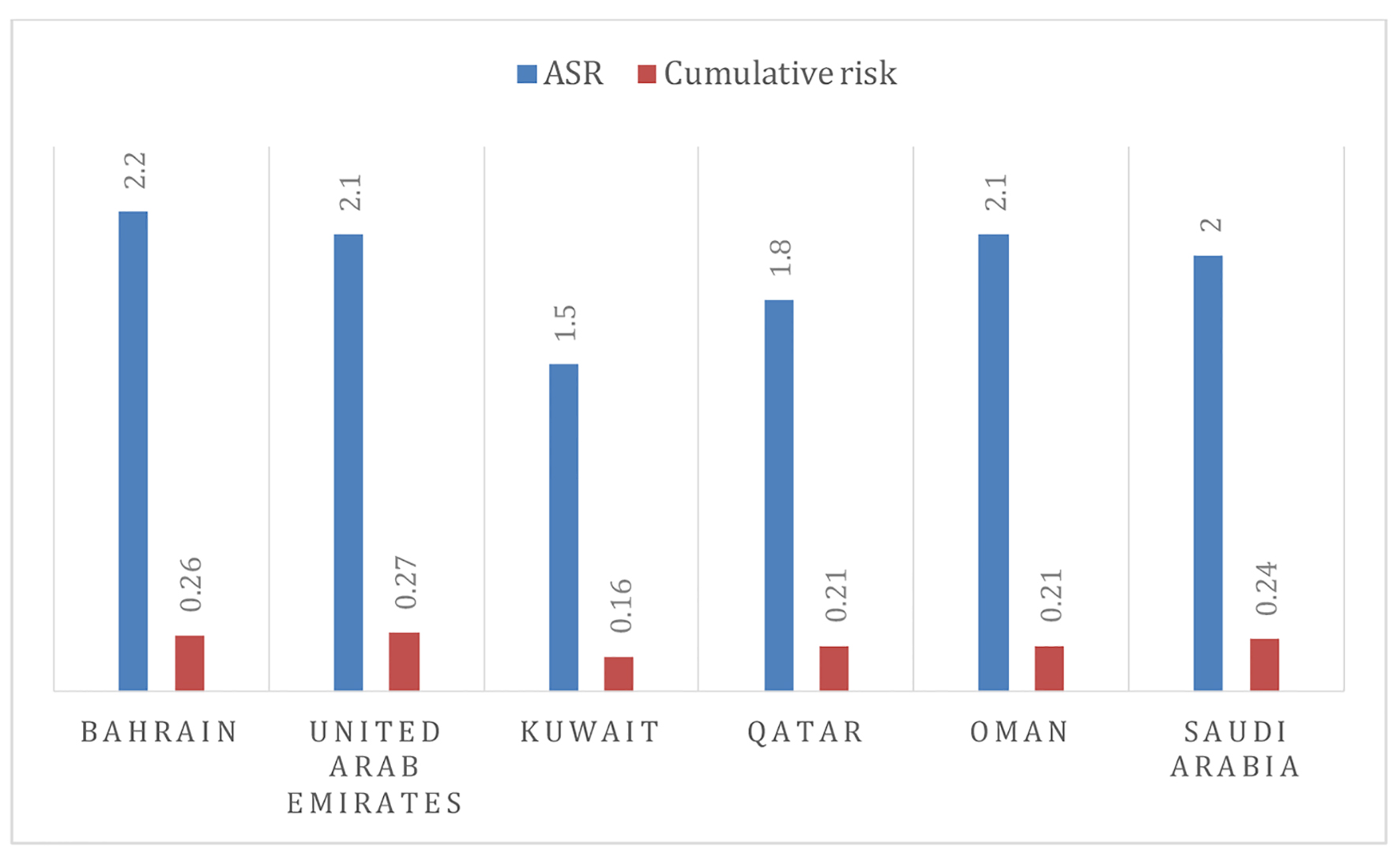

There is a relatively complete paucity of published data on O-OPCs from Arabian Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states. The available published literature is either from Middle East Region or on separate cancer entities (anatomical sites) from the O-OPCs group. According to GLOBOCAN report 2012, O-OPCs ranked among the top 20 cancers and accounted for 1.5% of all human cancers with a male to female ratio of 1.38:1.00 in the Middle East and North Africa [8-10]. However, the estimated age-standardized rates (ASRs) for O-OPCs in GCC countries were described in Figure 1 [8, 9]. The most frequently discussed cancer entity in GCC countries is oral cancer. In Arab countries, the prevalence rates of oral cancer were counted in a range of 1.8 to 2.13 per 100,000 individuals, with tobacco use, alcohol consumption, solar radiation and HPV being the possible risk factors [9, 11]. Detailed available information regarding epidemiology and possible risk factors of O-OPCs in GCC countries will be explored in this review.

Click for large image | Figure 1. The age-standardized rates and cumulative risk of O-OPCs in GCC member states [8, 9]. |

| Methodology | ▴Top |

Search strategy

Data published after 2008 related to O-OPCs in GCC countries were obtained through electronic searches in Medline/PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE) and Google Scholar. Keywords related to the association between O-OPCs metrics (epidemiology and risk factors) and GCC countries were used for electronic searches. Relevant keywords (oral cancer, oral cavity cancer, oropharyngeal cancer, epidemiology, risk factor, incidence, etc.) were used during the electronic search pertaining to the GCC countries (Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman and Saudi Arabia). No filters were used during the electronic searches.

Selection of required publications

In-depth selection was made through the search engine following effective inclusion and exclusion criteria to establish the possible facts in this review.

Inclusion criteria

Electronically available literature published after 2008 and related to epidemiology and risk factors of O-OPCs from GCC states members were included. Only English written literature was included.

Exclusion criteria

Literature reported from other Gulf countries (other than GCC states) was excluded. Literature pertaining to non-cancerous oropharyngeal disorders, laboratory research including animal trials, was excluded.

Quality appraisal

After scanning the titles of all relevant publications and reading the abstracts of the selected publications, full-text papers were appraised by the assigned reviewers using PRISMA guidelines [12].

Assessment of heterogeneity

Valid statistical package (Comprehensive Meta-analyses ver. 3) was used to calculate the summary effect estimate and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to test for heterogeneity [13, 14].

| Results and Discussion | ▴Top |

Epidemiology

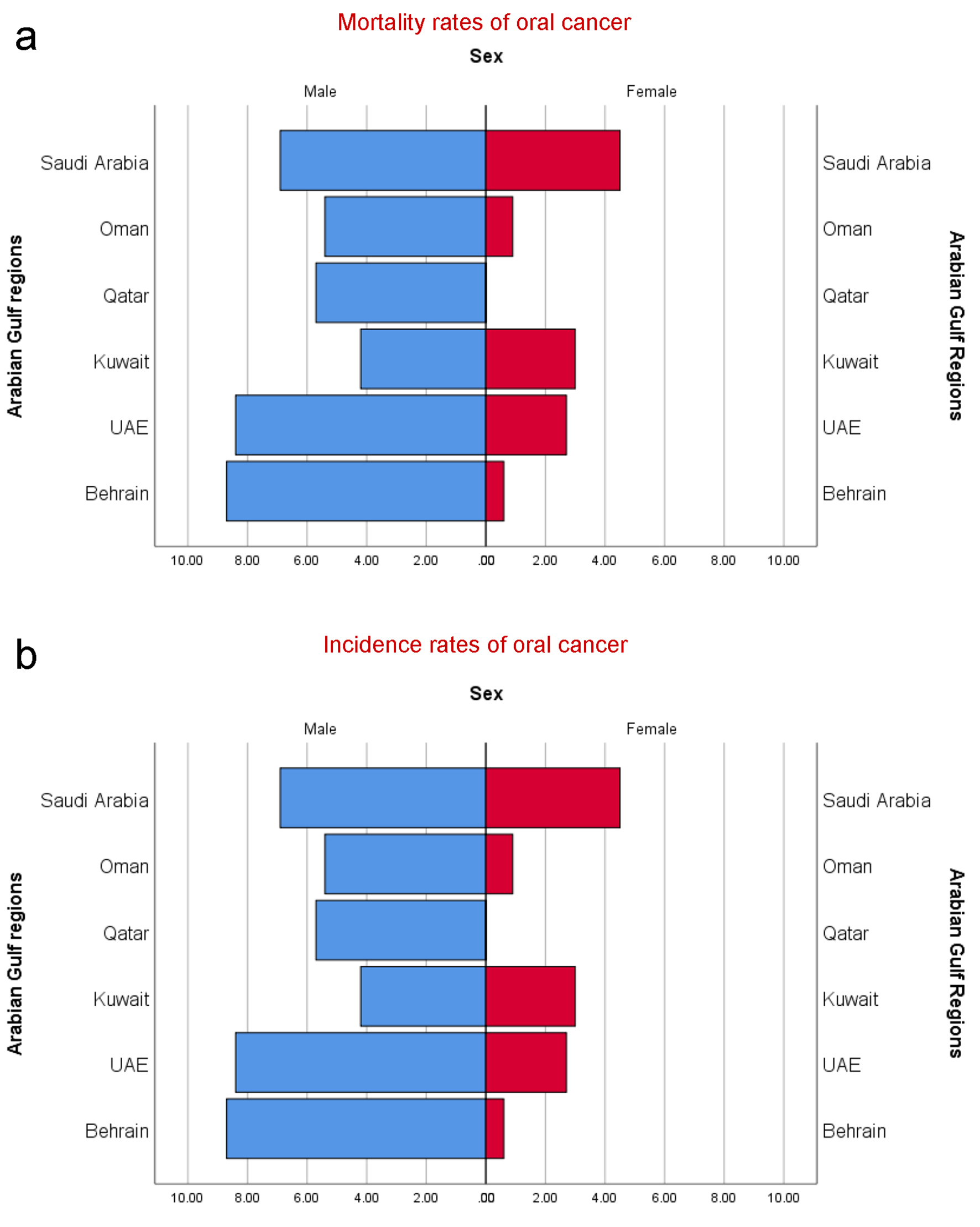

In the GCC countries, the incidence rates of O-OPCs were estimated to be 1,268 (896 males and 372 females) with ASR incidence rates of 0.1 - 3.2 in males and 0.1 - 1.3 in females [15]. The ASR mortality rates in the GCC countries ranged 0.1 - 1.8 in males and 0.1 - 0.7 in females with a male to female ratio of 2.41:1.00 and 2.59:1.00 for incidence and mortality rates, respectively [9, 10, 15]. The trends in the variations of O-OPCs among the GCC countries are shown in Table 1 [10, 13, 16-23]. The highest incidence rates and mortality rates of O-OPCs per 100,000 males were perceived in Saudi Arabia, representing 574 and 222 persons, followed by the United Arab Emirates (154 and 49), in this order. Similarly, among females, the highest incidence rates and mortality rates were encountered in Saudi Arabia (292 and 106) followed by the United Arab Emirates (39 and 10). According to recent estimates [24], the highest age-standardized incidence rates for O-OPCs were seen in Bahrain (3.2) followed by the United Arab Emirates (2.4) (Fig. 2). The highest oral cancer associated age-standardized death rates with respect to all cancers types are noticed in Saudi Arabia (1.74) followed by United Arab Emirates (1.24) then Qatar (1.21), Oman (0.89), Bahrain (0.80) and Kuwait (0.63). The epidemiological parameters including incidence, prevalence, mean age at diagnosis, histological types of cancer and risk factors are represented in Table 1.

Click to view | Table 1. Incidence, Prevalence and Possible Risk Factors of O-OPCs in GCC Countries |

Click for large image | Figure 2. (a) Estimated age-standardized mortality rates of oral cancer individuals (CID-10: C00-C08) in GCC countries per 100,000 persons. (b) Estimated age-standardized incidence rates of oral cancer individuals (CID-10: C00-C08) in GCC countries per 100,000 persons. |

Meta-analyses

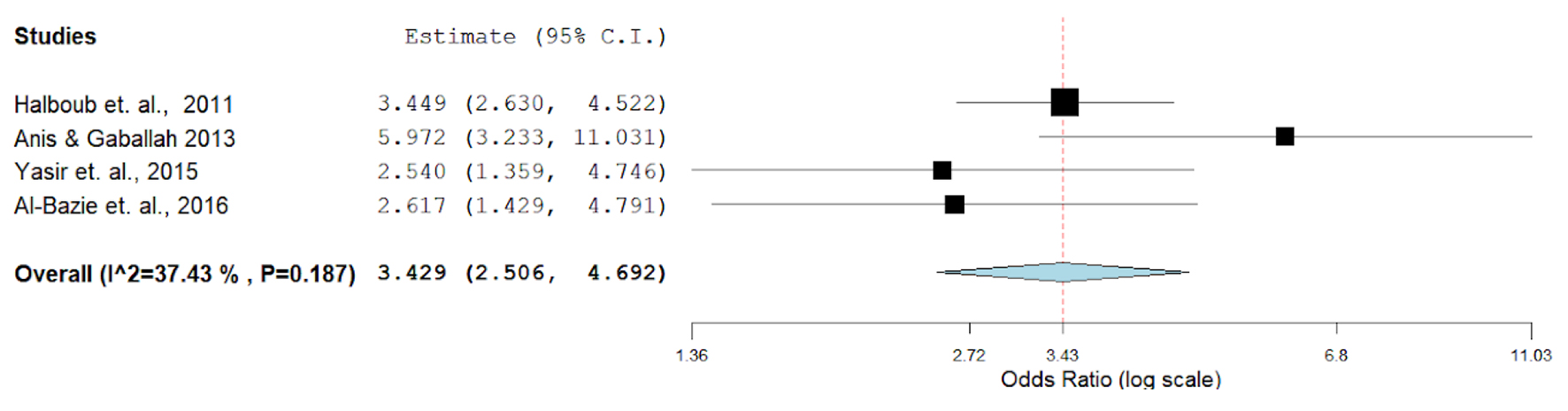

The overall prevalence of O-OPCs indicated a pooled odds ratio (OR) of 0.43 (95% CI: 43.2 - 51.4) in a series of seven studies performed after the year 2008. Studies in 2013 - 2017 revealed a pooled OR of 0.613 (95% CI: 5.78 - 7.03); moreover, studies after the year 2017 indicated a pooled OR (95% CI) of 0.75 (5.02 - 7.6), indicating a significant increase in the prevalence (P < 0.001) (Table 1, Fig. 3). The prevalence significantly increased over time in Saudi Arabia (P < 0.003) and United Arab Emirates (P < 0.002). Data were insufficient for Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and Oman, and as a result, trend analyses over time could not be performed for these regions. However, in Figure 3, the pooled four studies showed the overall P-value is 0.187, suggesting no a significant difference, which might be due to the small number of studies or insufficiency of data in this context. The prevalence of O-OPCs differed by the country of recruitment demonstrating an overall pooled OR (95% CI) of 0.399 (2.83 - 4.82) in Saudi Arabia and 0.505 (5.00 - 7.21) in the United Arab Emirates. These differences in the prevalence rates were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Meta-analyses (forest plot) of prevalence rates with respect to the report’s country. |

Etiology

In the GCC region, the etiology of O-OPC has been attributed to multifarious factors. Frequently investigated risk factors are the growing usage of various tobacco forms, alcohol consumption [10], HPV infection [25], genetic factors [26] and dietary factors [27]. Besides, gender and age, physical activity [28] and environmental factors [29] also play a crucial role in the progression of the disease. Though alcohol is strictly prohibited in these countries, the role of alcohol in O-OPCs cannot be ruled out.

Genetic factors and molecular pathogenesis

The molecular mechanism of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is still unclear. However, few studies on the mechanism for cell proliferation resulting in carcinogenesis have revealed the role of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in regulating the initiation and development of OSCC [30]. Recently polymorphism in the EPHX1 gene encoding microsomal epoxide hydrolase has been attributed to causing many cancers including OPC [31]. The role of miRNAs [32], overexpression of RNA TUG1 [33] has also been attributed to the progression of OSCC.

Biological factors

Viruses infection

One of the most comprehensively studied viruses to be involved in the carcinogenesis of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma depending on molecular and epidemiological data is HPV [34-36]. It was found that the combined effect of HPV-16 and tobacco boost up oral cancer risk. Analysis of OR (95% CI) was only available for one related study [18] with an estimated OR (95% CI) of 3.13 (3.13 - 4.5). The risk difference in the study was 0.28 with PLN 0.639. Although it was reported that OPC Saudi cases harbored around 21% of HPV (the global 36-46%) [37], some recent studies from Saudi Arabia reported an absence of HPV particularly in oral cancerous and precancerous lesions [38, 11]. However, the HPV-associated O-OPCs literature from GCC is insufficient to compute statistically signified-values.

Bacterial infection

The oral mucosa-harboring microorganisms greatly vary in their features, from beneficial effects to carcinogenic effects [39]. Oral microflora may proliferate in oral mucosa, tongue and even the pharyngeal regions altering the oral epithelium making them vulnerable to local and systemic infection leading to carcinogenesis [40]. Several studies reported the responsibility of the oral pathogenic microbes in the development of atheromatous plaques, periodontitis and other systemic diseases leading to carcinogenesis [39, 41].

Chemical factors

Tobacco use

Tobacco use is a leading cause of mortality through diverse complex diseases including cancer. In a study that included 1.2 million participants, 566 genetic variants in 406 loci were identified associated with different tobacco use phases (initiation, cessation and heaviness) [42]. Both smoked and smokeless tobacco was found to cause O-OPCs, with elevated potentiality in the oral cavity [43, 44]. The most tobacco-associated oral cancer is being OSCC, particularly among smokeless tobacco users [45-47].

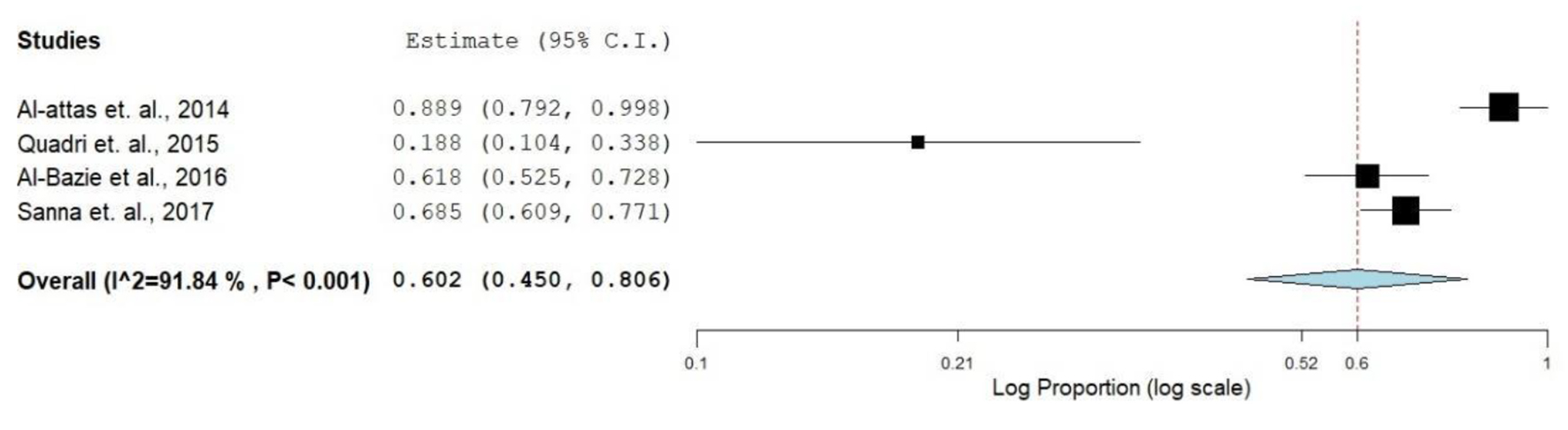

Increasing trends in smoking among GCC countries’ populations were reported in several publications [48-50]. Available evidence suggests that alternative tobacco products such as hookah, shisha and narghile have been widely used by the young generation in the GCC countries and might be one of the common risk factors for oral cancer [51]. A report from the United Arab Emirates showed cigarette smoking prevalence rates of 24.3% for males and 0.8% for females [52]. The prevalence rates of shisha (water pipe) smoking ranged 20-50% among men and 5-12% among women [53]. Though there is a scarcity of concrete evidence on the use of waterpipe smoking with cancer, few studies claimed its association with several types of cancerous conditions including nasopharyngeal cancer and oral dysplasia [54]. Midwakh use was the most common tobacco product used after cigarettes, and the users were predominantly men [55]. Shammah is another smokeless tobacco product comprised of tobacco, lime and black pepper mixture. Shammah is very popular in Yemen and Southern Saudi Arabia [16, 17, 56]. A total of four publications included in the review contained data from which OR was calculated on the risk of smoking (smoke/smokeless) and oral cancer. The overall prevalence of O-OPCs due to the use of tobacco or tobacco product (Table 1, Fig. 4) was 91.9%, the OR for both adjusted and non-adjusted varied from 0.19 (0.11 - 0.34) to 0.89 (0.78 - 1.0).

Click for large image | Figure 4. Forest plot of smoking and risk of oral cancer. |

Alcohol consumption

Even though several studies established the carcinogenic effect of alcohol, it is not considered a direct carcinogen. However, some compounds of alcoholic beverages such as acetaldehyde, benzene, ethanol and formaldehyde are known to cause cancer in humans and its potentiality increases when used in combination with tobacco products [57]. Though there are strong legislation and ban on the alcoholic beverage in GCC countries, globalization has led to its importation in some countries. The consumption of alcoholic beverages is more prevalent among young people [58].

Catha edulis, khat plant consumption

The chewing of leaves and twigs of Khat (Catha edulis) is commonly practiced among inhabitants of Yemen and East Africa [59, 60]. Although there is no direct correlation between the use of khat and the prevalence of oral cancer, studies from the region claimed its association with oral cancer [52, 57, 61].

However, there are ongoing efforts toward O-OPCs prevention and early detection in GCC member states. Changing lifestyles, lack of timely detection and awareness, poor treatment and access to palliative care are among the multitude of factors challenging the cancer patients. Poor database on incidence and mortality is another hurdle to mitigate the problem. Awareness among the public, implementation of effective health policies and timely action of healthcare practitioners (HCPs) may minimize the risk of O-OPCs [62, 63].

Conclusion

There is a tremendous paucity of epidemiological data relating to O-OPCs as a group from GCC countries. The available epidemiologic data show relatively higher O-OPCs prevalence rates in GCC countries with some sorts of diversity among these countries. Besides the general O-OPCs risk factors, there are some risk factors pertained to the region, such as Shammah and Khat. This review represents a major source of O-OPCs-related data about GCC countries, which may orient further search in this context.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Wedad Saeed Alqahtani and Nawaf Abdulrahman Almufareh: conceptual, data search, drafting and approval of final version. Halah A. Al-Johani and Bassam Ahmed Almutlaq: conceptual, data search and approval of final version. Rasil Khaled Alotaibi, Consul Iworikumo Juliana, Nada Hamad Aljarba and Bandary Almarshedy: conceptual, data search, analysis and approval of final version. Abdulqader Saeed Alqahtani, Abdelbaset Mohamed Elasbali: data search, revision and approval of final version. Hussain Gadelkarim Ahmed: conceptual, data search, drafting, revision and approval of final version.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(4-5):309-316.

doi pubmed - Hussein AA, Helder MN, de Visscher JG, Leemans CR, Braakhuis BJ, de Vet HCW, Forouzanfar T. Global incidence of oral and oropharynx cancer in patients younger than 45 years versus older patients: A systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2017;82:115-127.

doi pubmed - Shield KD, Ferlay J, Jemal A, Sankaranarayanan R, Chaturvedi AK, Bray F, Soerjomataram I. The global incidence of lip, oral cavity, and pharyngeal cancers by subsite in 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):51-64.

doi pubmed - Conway DI, Purkayastha M, Chestnutt IG. The changing epidemiology of oral cancer: definitions, trends, and risk factors. Br Dent J. 2018;225(9):867-873.

doi pubmed - Tanaka TI, Alawi F. Human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. Dent Clin North Am. 2018;62(1):111-120.

doi pubmed - Zini A, Czerninski R, Sgan-Cohen HD. Oral cancer over four decades: epidemiology, trends, histology, and survival by anatomical sites. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39(4):299-305.

doi pubmed - Amarasinghe HK, Usgodaarachchi U, Kumaraarachchi M, Johnson NW, Warnakulasuriya S. Diet and risk of oral potentially malignant disorders in rural Sri Lanka. J Oral Pathol Med. 2013;42(9):656-662.

doi pubmed - Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CANCERBase No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. http://globocan.iarc.fr (accessed 02 December 2019).

- Al-Jaber A, Al-Nasser L, El-Metwally A. Epidemiology of oral cancer in Arab countries. Saudi Med J. 2016;37(3):249-255.

doi pubmed - Kujan O, Farah CS, Johnson NW. Oral and oropharyngeal cancer in the Middle East and North Africa: Incidence, mortality, trends, and gaps in public databases as presented to the Global Oral Cancer Forum. Translational Research in Oral Oncology. 2017;2:1-9.

doi - Lerman MA, Almazrooa S, Lindeman N, Hall D, Villa A, Woo SB. HPV-16 in a distinct subset of oral epithelial dysplasia. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(12):1646-1654.

doi pubmed - PRISMA statement on transparent reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. http://www.prisma-statement.org/, accessed May 7, 2018.

- Anis R, Gaballah K. Oral cancer in the UAE: a multicenter, retrospective study. Libyan J Med. 2013;8:21782.

doi - McClure SA, Movahed R, Salama A, Ord RA. Maxillofacial metastases: a retrospective review of one institution's 15-year experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(1):178-188.

doi pubmed - GLOBOCAN: estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. International Agency for Research on Cancer [online]. 2012. [cited 2016 July 16] Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_population.aspx, accessed December 2, 2019.

- Halboub ES, Al-Anazi YM, Al-Mohaya MA. Characterization of Yemeni patients treated for oral and pharyngeal cancers in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2011;32(11):1177-1182.

- Saleh SM, Idris AM, Vani NV, Tubaigy FM, Alharbi FA, Sharwani AA, Mikhail NT, et al. Retrospective analysis of biopsied oral and maxillofacial lesions in South-Western Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(4):405-412.

doi pubmed - Vaccarella S, Bruni L, Seoud M. Burden of human papillomavirus infections and related diseases in the extended Middle East and North Africa region. Vaccine. 2013;31(Suppl 6):G32-44.

doi pubmed - Al-Attas SA, Ibrahim SS, Amer HA, Darwish Zel S, Hassan MH. Prevalence of potentially malignant oral mucosal lesions among tobacco users in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(2):757-762.

doi pubmed - Quadri MF, Mahnashi A, Al Almutahhir A, Tubayqi H, Hakami A, Arishi M, Alamir A. Association of Awake Bruxism with Khat, Coffee, Tobacco, and Stress among Jazan University Students. Int J Dent. 2015;2015:842096.

doi pubmed - Al-Bazie SA, Bahatheq M, Al-Ghazi M, Al-Rajhi N, Ramalingam S. Antibiotic protocol for the prevention of osteoradionecrosis following dental extractions in irradiated head and neck cancer patients: A 10 years prospective study. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016;12(2):565-570.

doi pubmed - Hesham A, Syed KB, Jamal BT, Alqahtani AM, Alfaqih AA, Alshehry HA, Hameed MS. Incidence, clinical presentation, and demographic factors associated with oral cancer patients in the southern region of Saudi Arabia: A 10-year retrospective study. J Int Oral Health. 2017;9:105-109.

- Al Sarraj Y, Nair SC, Al Siraj A, AlShayeb M. Characteristics of salivary gland tumours in the United Arab Emirates. Ecancermedicalscience. 2015;9:583.

doi pubmed - World Health Rankings, Live longer live better. Available from: http://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/middle-east/oral-cancer-cause-of-death. Accessed May 21, 2018.

- Bozinovic K, Sabol I, Rakusic Z, Jakovcevic A, Sekerija M, Lukinovic J, Prgomet D, et al. HPV-driven oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer in Croatia - Demography and survival. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0211577.

doi pubmed - Ando M, Saito Y, Xu G, Bui NQ, Medetgul-Ernar K, Pu M, Fisch K, et al. Chromatin dysregulation and DNA methylation at transcription start sites associated with transcriptional repression in cancers. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2188.

doi pubmed - Irimie AI, Braicu C, Pasca S, Magdo L, Gulei D, Cojocneanu R, Ciocan C, et al. Role of key micronutrients from nutrigenetic and nutrigenomic perspectives in cancer prevention. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(6):283.

doi pubmed - McNeely ML. Exercise as a promising intervention in head & neck cancer patients. Indian J Med Res. 2013;137(3):451-453.

- Kudo Y, Tada H, Fujiwara N, Tada Y, Tsunematsu T, Miyake Y, Ishimaru N. Oral environment and cancer. Genes Environ. 2016;38:13.

doi pubmed - Zhao X, Sun S, Zeng X, Cui L. Expression profiles analysis identifies a novel three-mRNA signature to predict overall survival in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res. 2018;8(3):450-461.

- Lakkakula S, Maram R, Munirajan AK, Pathapati RM, Visweswara SB, Bhaskar VKS Lakkakula. EPHX1 gene polymorphisms among south Indian populations. Mol Cell Toxicol. 2013;9:219-225.

doi - Yang X, Ruan H, Hu X, Cao A, Song L. miR-381-3p suppresses the proliferation of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells by directly targeting FGFR2. Am J Cancer Res. 2017;7(4):913-922.

- Yan G, Wang X, Yang M, Lu L, Zhou Q. Long non-coding RNA TUG1 promotes progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma through upregulating FMNL2 by sponging miR-219. Am J Cancer Res. 2017;7(9):1899-1912.

- Pirotte EF, Holzhauser S, Owens D, Quine S, Al-Hussaini A, Christian AD, Giles PJ, et al. Sensitivity to inhibition of DNA repair by Olaparib in novel oropharyngeal cancer cell lines infected with Human Papillomavirus. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0207934.

doi pubmed - Gao G, Wang J, Kasperbauer JL, Tombers NM, Teng F, Gou H, Zhao Y, et al. Whole genome sequencing reveals complexity in both HPV sequences present and HPV integrations in HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):352.

doi pubmed - IARC Working Group on the evaluation of carcinogenic risk to humans. Biological Agents. Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2012. (IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, No. 100B.) Human Papillomaviruses. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304347/, accessed December 3, 2019.

- Alsbeih G, Al-Harbi N, Bin Judia S, Al-Qahtani W, Khoja H, El-Sebaie M, Tulbah A. Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection and the Association with survival in saudi patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(6):820.

doi pubmed - Nasher AT, Al-Hebshi NN, Al-Moayad EE, Suleiman AM. Viral infection and oral habits as risk factors for oral squamous cell carcinoma in Yemen: a case-control study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;118(5):566-572 e561.

doi pubmed - Ramakrishnaiaha R, Durgesha BH, Basavarajappaa S, Al Kheraifa AA, Divakarb DD. Genetic, molecular and microbiological aspects of oral cancer. Reviews in Medical Microbiology. 2015;26:134-137.

doi - Meurman JH. Oral microbiota and cancer. J Oral Microbiol. 2010;2.

doi pubmed - Bengmark S. Gut microbiota, immune development and function. Pharmacol Res. 2013;69(1):87-113.

doi pubmed - Liu M, Jiang Y, Wedow R, Li Y, Brazel DM, Chen F, Datta G, et al. Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat Genet. 2019;51(2):237-244.

doi pubmed - Kjaerheim K, Haldorsen T, Lynge E, Martinsen JI, Pukkala E, Weiderpass E, Grimsrud TK. Variation in Nordic work-related cancer risks after adjustment for alcohol and tobacco. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(12).

doi pubmed - Asthana S, Labani S, Kailash U, Sinha DN, Mehrotra R. Association of smokeless tobacco use and oral cancer: a systematic global review and meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(9):1162-1171.

doi pubmed - Rimal J, Shrestha A, Maharjan IK, Shrestha S, Shah P. Risk assessment of smokeless tobacco among oral precancer and cancer patients in Eastern Developmental Region of Nepal. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20(2):411-415.

doi pubmed - Zhang Y, He J, He B, Huang R, Li M. Effect of tobacco on periodontal disease and oral cancer. Tob Induc Dis. 2019;17:40.

doi pubmed - Jiang X, Wu J, Wang J, Huang R. Tobacco and oral squamous cell carcinoma: A review of carcinogenic pathways. Tob Induc Dis. 2019;17:29.

doi pubmed - Al Makadma AS. Adolescent health and health care in the Arab Gulf countries: Today's needs and tomorrow's challenges. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2017;4(1):1-8.

doi pubmed - Awan KH, Hussain QA, Khan S, Peeran SW, Hamam MK, Hadlaq EA, Bagieh HA. Accomplishments and challenges in tobacco control endeavors - Report from the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Saudi Dent J. 2018;30(1):13-18.

doi pubmed - Ahmed AE, Alwadey AM, Areabi HA. Validation of Arabic questionnaire on impact of gulf council countries cigarette package warning labels. Journal of International Oral Health. 2016;8(3):313-318.

- Maziak W. The waterpipe: an emerging global risk for cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37(1):1-4.

doi pubmed - Al-Houqani M, Ali R, Hajat C. Tobacco smoking using Midwakh is an emerging health problem - evidence from a large cross-sectional survey in the United Arab Emirates. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39189.

doi pubmed - Rastam S, Li FM, Fouad FM, Al Kamal HM, Akil N, Al Moustafa AE. Water pipe smoking and human oral cancers. Med Hypotheses. 2010;74(3):457-459.

doi pubmed - Akl EA, Gaddam S, Gunukula SK, Honeine R, Jaoude PA, Irani J. The effects of waterpipe tobacco smoking on health outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(3):834-857.

doi pubmed - Vupputuri S, Hajat C, Al-Houqani M, Osman O, Sreedharan J, Ali R, Crookes AE, et al. Midwakh/dokha tobacco use in the Middle East: much to learn. Tob Control. 2016;25(2):236-241.

doi pubmed - Alsanosy RM. Smokeless tobacco (shammah) in Saudi Arabia: a review of its pattern of use, prevalence, and potential role in oral cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(16):6477-6483.

doi pubmed - Petti S, Masood M, Messano GA, Scully C. Alcohol is not a risk factor for oral cancer in nonsmoking, betel quid non-chewing individuals. A meta-analysis update. Ann Ig. 2013;25(1):3-14.

- Musaiger AO, Takruri HR, Hassan AS, Abu-Tarboush H. Food-based dietary guidelines for the arab gulf countries. J Nutr Metab. 2012;2012:905303.

doi pubmed - Gupta B, Johnson NW. Systematic review and meta-analysis of association of smokeless tobacco and of betel quid without tobacco with incidence of oral cancer in South Asia and the Pacific. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e113385.

doi pubmed - IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Betel-quid and areca-nut chewing and some areca-nut derived nitrosamines. IARC, Lyon. 2006;85. Available from: https://publications.iarc.fr/_publications/media/download/2683/6e3997066d7dd40048c519550cfb2ad627aac6f0.pdf, Accessed December 3, 2019.

- Sepetdjian E, Shihadeh A, Saliba NA. Measurement of 16 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in narghile waterpipe tobacco smoke. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46(5):1582-1590.

doi pubmed - Jaber L, Shaban S, Hariri D, Smith S. Perceptions of healthcare practitioners in Saudi Arabia regarding their training in oral cancer prevention, and early detection. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2011;24(1):8-18.

doi pubmed - Joseph BK, Sundaram DB, Ellepola AN. Assessing oral cancer knowledge among undergraduate dental students in Kuwait University. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30(3):415-420.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

World Journal of Oncology is published by Elmer Press Inc.