| World Journal of Oncology, ISSN 1920-4531 print, 1920-454X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, World J Oncol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.wjon.org |

Case Report

Volume 3, Number 4, August 2012, pages 194-198

Early Recognition of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome Leads to Avoidance of Endotracheal Intubation

Johan Barrettoa, Baldeep Wirkb, c

aUniversity of Florida, Department of Medicine, College of Medicine USA

bUniversity of Florida, Division of Hematology-Oncology, College of Medicine, USA

cCorresponding author: Baldeep Wirk, University of Florida, Division of Hematology-Oncology, 1600 SW Archer Road, POBOX 100277, Gainesville, FL 32610, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication June 14, 2012

Short title: IRIS in Hematological Malignancy Patients

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/wjon527w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome occurs in patients with rapidly recovering immune systems in response to antigens (viable pathogens, nonviable pathogen debris, host antigens or tumor antigens). The acronym IRIS, Greek for spectrum of color, is often used for immune reconstitution inflammatory response syndrome and reflects the wide spectrum of clinical manifestations associated with this entity. This is a case report of an acute myelogenous leukemia patient with neutropenia after cytotoxic chemotherapy who developed severe dyspnea and new pulmonary infiltrates temporally associated with rapid neutrophil recovery. The incidence, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and therapy of IRIS will be discussed in this article. There should be an increased awareness of the many clinical manifestations of IRIS in hematologic malignancy patients with rapid neutrophil recovery after cytotoxic chemotherapy, in order to allow prompt institution of corticosteroids which could be life saving.

Keywords: Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; IRIS; Neutrophil recovery; Chemotherapy

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome is also known by the acronym IRIS, Greek for spectrum of color. Indeed IRIS has a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. IRIS is an inflammatory response to antigens (viable pathogens, nonviable pathogen debris, host antigens or tumor antigens) in patients with rapidly recovering immune systems [1]. IRIS can be unmasking of covert infections in immunosuppressed hosts who cannot mount an immune response to viable pathogens until immune system recovery. In paradoxical IRIS, there is clinical deterioration of an infection despite effective antimicrobials and is caused by restoration of the immune response to antigens from dying nonviable pathogens [1]. This article highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in hematologic malignancy patients with rapid neutrophil recovery after cytotoxic chemotherapy. This could avoid erroneous changes in antimicrobial therapy and allow prompt institution of corticosteroids which could be life saving.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 56 years old Caucasian female with no prior medical history developed acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), CD13+, CD33+, CD11+, cytogenetics 46 XX, with FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3-internal tandem duplication and nucleophosmin 1 mutation. Although she had primary induction failure to idarubicin and cytarabine (ara-c), she had complete remission to fludarabine, ara-c, idarubicin with granulocyte colony stimulating factor (FLAG-I). Then FLAG-I consolidation was given. Neutropenic fever (39 °C) developed 11 days after start of consolidation chemotherapy when the neutrophil count was zero. Cefepime was begun. Blood cultures showed vancomycin resistant enterococci faecium (VRE) sensitive to linezolid and this was added. Fluconazole 400 mg a day and acyclovir 800 mg twice a day as neutropenic prophylaxis were given. Serum galactomannan index (GMI), fungal blood cultures and urine cultures were negative. Chest computerized tomography (CT) was unremarkable. The central line was removed and the VRE bacteremia cleared. Fever resolved. Transesophageal echocardiogram showed no vegetations. Renal and liver function tests were normal. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCSF) was continued. Neutropenia resolved 15 days after start of consolidation chemotherapy when the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was 850/microliter. GCSF was discontinued on day 16 when the white blood cell count was 4200/microliter, neutrophil count 1800/microliter, hemoglobin 10.3 g/dL, platelets 46,000/microliter. The ANC rose to 4800/microliter within 4 days from a nadir of zero.

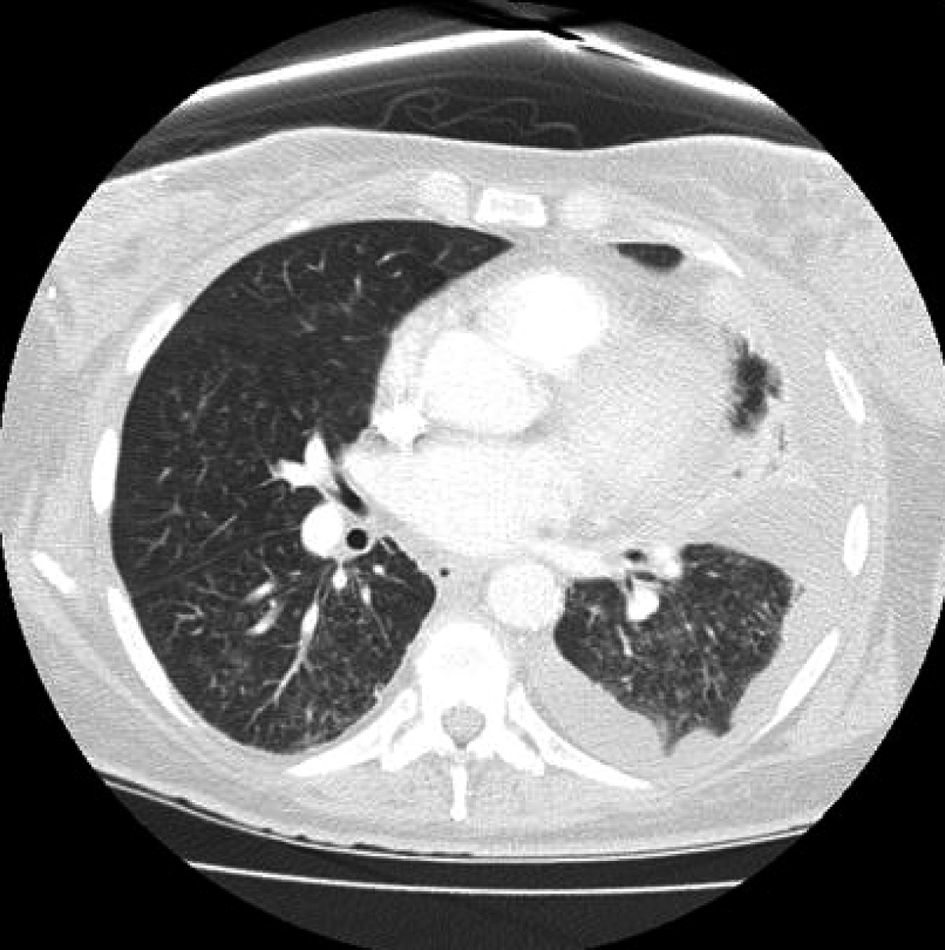

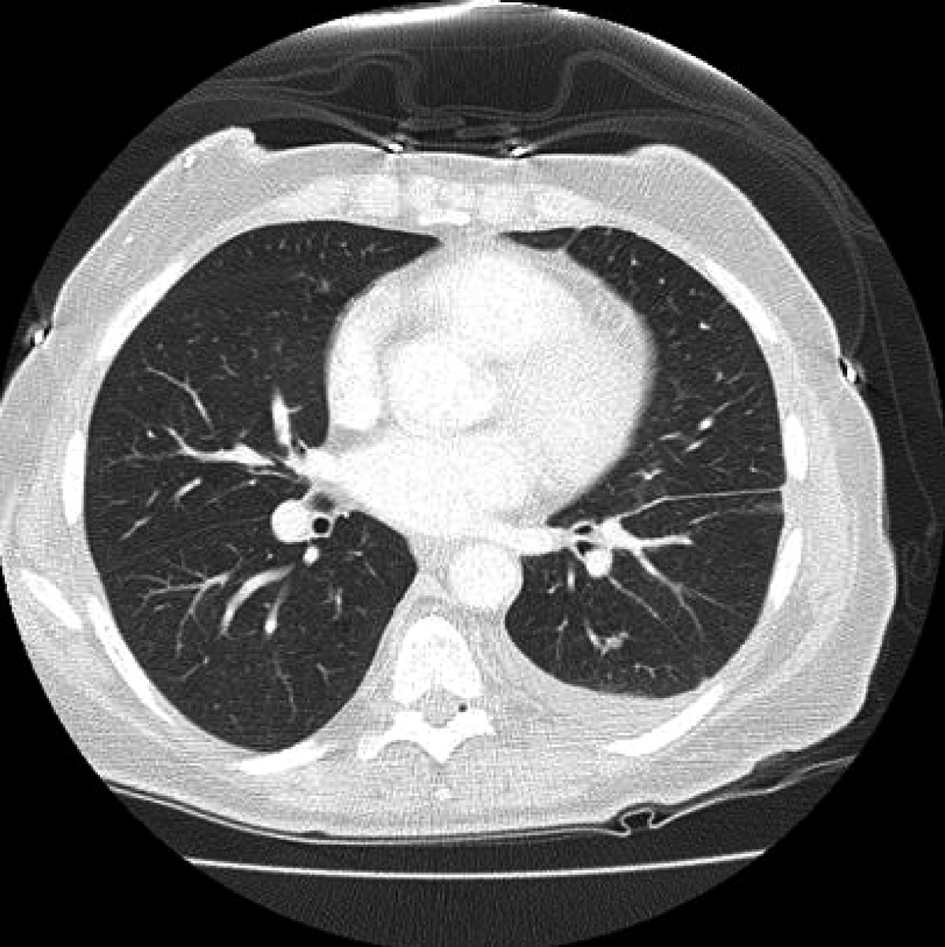

On day 16 after consolidation, sudden onset of dyspnea (PO2 60 mmHg, oxygen saturation 80%, PCO2 57 mmHg) and fever (38.3 degrees Celsius) developed. Blood pressure was 125/68, heart rate 80 beats/minute, and respirations 18/minute. No recent blood transfusions had been given for 3 days. Chest CT showed diffuse interstitial infiltrates and a new left sided pleural effusion suggestive of atypical pneumonia (Fig. 1). CT abdomen showed no hepatosplenic lesions. Cefepime, linezolid were continued and azithromycin added. After intensive care unit (ICU) transfer, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (BIPAP) was begun. Echocardiogram showed left ventricular ejection fraction 55-60%. Bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) showed no growth on bacterial, fungal or mycobacterial cultures. Serum cytomegalovirus deoxyribonucleic acid polymerase chain reaction (CMV DNA PCR) and adenovirus DNA PCR were negative. BAL was negative for respiratory viruses by PCR (influenza A and B, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, human metapneumonovirus, rhinovirus, and adenovirus). Transbronchial biopsy was not done due to thrombocytopenia. Aerobic, anaerobic, fungal and mycobacterial blood and sputum cultures were negative. Diagnostic thoracentesis of a 100 mL was transudative with negative bacterial, fungal and mycobacterial cultures. Gomori methenamine silver stain, acid fast bacilli stain and Fite stain were negative on the BAL and pleural fluid and there was no evidence of Pneumocystis jirovecii or nocardiosis. Furosemide had no response. Given the negative infectious workup and the correlation of her acute respiratory symptoms with neutrophil recovery, methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg/ day was given for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). She improved dramatically in 24 hours. BIPAP was discontinued. She was discharged from the ICU the next day and went home 4 days later on a tapering course of prednisone without the need for supplemental oxygen. Chest CT showed good resolution of the pleural effusion and interstitial infiltrates (Fig. 2). Prompt identification of IRIS and initiation of corticosteroids led to avoidance of mechanical ventilation and possibly a prolonged ICU course.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Sudden onset of diffuse interstitial infiltrates and left sided pleural effusion. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Prompt resolution of infiltrates and pleural effusion after start of corticosteroids. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Incidence of iris

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients given antiretroviral therapy have a 10-25% incidence of IRIS due to recovery of CD4+ lymphocyte levels and adaptive immunity [2]. IRIS also occurs in other populations with rapidly recovering immune systems such as neutropenic hematological malignancy patients after neutrophil recovery, solid organ and hematopoietic cell transplant recipients after immunosuppression withdrawal, post partum women, and with cessation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) antagonist therapy [3]. Pathogenesis of IRIS is poorly understood (Table 1). Possible mechanisms include host immunity restoration during effective antimicrobial therapy which potentiates a shift from dominant T helper (Th) responses that are anti- inflammatory (Th2 and regulatory T cells) to proinflammatory T cells (Th1 and Th17) [3]. Genetic predisposition with distinct human leukocyte antigen (HLA) profiles and gene polymorphisms of cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α have been implicated [4]. For example, HIV CMV retinitis or encephalitis IRIS was associated with human leukocyte antigen HLA A2, B44, and DR4 [4, 5]. Our patient did not have these HLA antigens. Elevation of serum interleukin (IL)-6 has been seen during IRIS irrespective of the provoking pathogen [5]. Leukotrienes, released by mast cells, may be involved in the pathogenesis of IRIS. IRIS associated with urticarial vasculitis and tuberculosis was treated with the leukotriene receptor antagonist monteleukast successfully [6]. IRIS has been linked with mycobacterial, viral and fungal organisms such as Mycobacterium avium, leprae or tuberculosis, cytomegalovirus, disseminated candidiasis, invasive aspergillosis, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis and Pneumocystitis jirovecii [2].

Click to view | Table 1. Pathogenesis of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome and Potential Therapeutic Approaches |

Clinical presentation

Neutropenic hematologic malignancy patients undergoing effective antifungal therapy for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) had a 4 fold increase in the mean volume of lung nodules in the first week with neutrophil recovery, associated with cavitation and the air crescent sign [7]. This is related to recovery of innate immunity and the lung damage is due to release of neutrophil proteases [7]. Patients with cavitation had better outcomes [7]. Neutrophil recovery in hematologic malignancy patients after cytotoxic chemotherapy can also lead to IRIS [8]. Nineteen hematological malignancy patients with neutropenia and proven/probable IPA, developed clinical (dyspnea, hypoxia with need for oxygen or mechanical ventilation, hemoptysis, chest pain) and radiological deterioration (pulmonary infiltrates, pleural effusions, lymphadenopathy, cavitation) associated with neutrophil recovery despite improving sequential serum GMI titers indicating treated IPA [8]. Onset of IRIS was at a mean of 2 days (range -8 to +15 days) from resolution of neutropenia to an absolute neutrophil count of > 500 /microliter [8]. In cases of IPA related IRIS, the rapidity of neutrophil recovery has been correlated with the degree of associated morbidity. In an Italian study of 20 neutropenic hematologic malignancy patients, the risk of pulmonary IRIS was higher when the ANC recovered from less than 100/microliter to greater than 4500/per microliter within a 5 day period as in our case [9]. The risk of developing IRIS was 75% with rapid ANC recovery versus 17% with more gradual recovery [5].

Undetected chronic disseminated candidiasis in neutropenic hematologic malignancy patients becomes apparent as fever, abdominal pain and hepatosplenic lesions with neutrophil recovery and is a manifestation of IRIS. Liver biopsy shows granulomas with T-cell infiltration and negative cultures [10]. In 10 patients with persistent chronic disseminated candidiasis despite 34 days of antifungal therapy, only corticosteroids resulted in resolution of fever and abdominal pain after a median of 4 days [11].

Therapy

IRIS therapy is based on case reports and small series. Prognosis of IRIS after neutrophil recovery in cancer patients is generally good, much like HIV IRIS which heralds immune reconstitution with diminishing HIV viral loads and better survival [8]. However, some patients with pulmonary IRIS develop respiratory failure and may not survive [8]. After excluding other infections, methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg/d intravenously for 3 - 7 days has been used successfully in IPA patients with IRIS and impending respiratory failure lending further support to the immune etiology of IRIS [8]. Corticosteroids reduce Th1 and expand anti-inflammatory Th2 and regulatory T cell populations [2]. A therapeutic benefit of TNF-α inhibitors has been seen in steroid refractory cases [12]. A patient with miliary tuberculosis treated effectively with antimicrobials, developed paradoxical brain and lymph nodes lesions that were refractory to prolonged high dose corticosteroids but responded to infliximab [12]. TNF-α activates macrophages which allow granuloma formation. TNF-α inhibition with infliximab contributed to the resolution of the neurologic symptoms, brain lesions and lymphadenopathy, which were biopsy proven granulomas, culture negative for Mycobacteria tuberculosis (paradoxical IRIS) [12]. Statins potentiate anti-inflammatory T helper responses (Th2 and regulatory T cells), reduce proinflammatory T cells (Th1 and Th17), diminish tissue neutrophil migration and could be useful in treating IRIS [13, 14]. Case reports have also shown leukotriene inhibitors (monteleukast) to be beneficial in treating IRIS [6].

Conclusions

No specific biomarkers to distinguish IRIS from progressive infection exist, making the timely diagnosis of lRIS challenging. Diagnosis of IRIS relies mainly on clinical criteria, such as temporal association of rapid neutrophil recovery with clinical and radiologic deterioration and exclusion of other causes such as infection (Table 2). In our patient, dyspnea and pulmonary infiltrates developed temporally associated with rapid neutrophil recovery (from ANC 0 to 4800/microliter in 4 days). After excluding infections, high dose corticosteroids were given to successfully avert respiratory failure. The etiology of pulmonary IRIS in our patient is unclear but may have been related to dying pathogen debris or tumor antigens. In hematologic malignancy patients with rapid neutrophil recovery after cytotoxic chemotherapy, maintaining a high index of suspicion for IRIS could avoid erroneous changes in antimicrobial therapy and allow prompt institution of corticosteroids which could be life saving.

Click to view | Table 2. When to Suspect Immune Reconstitution Syndrome in Hematologic Malignancy Patients Undergoing Cytotoxic Chemotherapy |

Acknowledgments

None.

Sources of Grant Support

None.

Financial Disclosures

None.

| References | ▴Top |

- Tappuni AR. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Adv Dent Res. 2011;23(1):90-96.

pubmed doi - Shelburne SA, Visnegarwala F, Darcourt J, Graviss EA, Giordano TP, White AC

Jr , Hamill RJ. Incidence and risk factors for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome during highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2005;19(4):399-406.

pubmed doi - Sun HY, Singh N. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in non-HIV immunocompromised patients. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22(4):394-402.

pubmed doi - Price P, Keane NM, Stone SF, Cheong KY, French MA. MHC haplotypes affect the expression of opportunistic infections in HIV patients. Hum Immunol. 2001;62(2):157-164.

pubmed doi - Price P, Morahan G, Huang D, Stone E, Cheong KY, Castley A, Rodgers M,

et al . Polymorphisms in cytokine genes define subpopulations of HIV-1 patients who experienced immune restoration diseases. AIDS. 2002;16(15):2043-2047.

pubmed doi - Lipman MC, Carding SK. Successful drug treatment of immune reconstitution disease with the leukotriene receptor antagonist, montelukast: a clue to pathogenesis?. AIDS. 2007;21(3):383-384.

pubmed doi - Caillot D, Couaillier JF, Bernard A, Casasnovas O, Denning DW, Mannone L, Lopez J,

et al . Increasing volume and changing characteristics of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis on sequential thoracic computed tomography scans in patients with neutropenia. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(1):253-259.

pubmed - Miceli MH, Maertens J, Buve K, Grazziutti M, Woods G, Rahman M, Barlogie B,

et al . Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in cancer patients with pulmonary aspergillosis recovering from neutropenia: Proof of principle, description, and clinical and research implications. Cancer. 2007;110(1):112-120.

pubmed doi - Todeschini G, Murari C, Bonesi R, Pizzolo G, Verlato G, Tecchio C, Meneghini V,

et al . Invasive aspergillosis in neutropenic patients: rapid neutrophil recovery is a risk factor for severe pulmonary complications. Eur J Clin Invest. 1999;29(5):453-457. - Thaler M, Pastakia B, Shawker TH, O'Leary T, Pizzo PA. Hepatic candidiasis in cancer patients: the evolving picture of the syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108(1):88-100.

pubmed - Blackmore TK, Manning L, Taylor WJ, Wallis RS. Therapeutic use of infliximab in tuberculosis to control severe paradoxical reaction of the brain and lymph nodes. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(10):e83-85.

pubmed doi - Falagas ME, Makris GC, Matthaiou DK, Rafailidis PI. Statins for infection and sepsis: a systematic review of the clinical evidence. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61(4):774-785.

pubmed doi - Maher BM, Dhonnchu TN, Burke JP, Soo A, Wood AE, Watson RW. Statins alter neutrophil migration by modulating cellular Rho activity—a potential mechanism for statins-mediated pleotropic effects?. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85(1):186-193.

pubmed doi - Maher BM, Dhonnchu TN, Burke JP, Soo A, Wood AE, Watson RW. Statins alter neutrophil migration by modulating cellular Rho activity—a potential mechanism for statins-mediated pleotropic effects?. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85(1):186-193.

doi

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

World Journal of Oncology is published by Elmer Press Inc.