| World Journal of Oncology, ISSN 1920-4531 print, 1920-454X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, World J Oncol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.wjon.org |

Original Article

Volume 11, Number 4, August 2020, pages 165-172

Distribution of Breast Cancer Subtypes Among Nigerian Women and Correlation to the Risk Factors and Clinicopathological Characteristics

Adeoluwa Akeem Adenijia, f, Olayemi Olubunmi Dawodub, Muhammad Yaqub Habeebuc, Ademola Oluwatosin Oyekana, Mariam Adebola Bashira, Mike G. Martind, Samuel Olalekan Keshinroe, Gabriel Timilehin Fagbenroa

aOncology and Radiotherapy Department, Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria

bMolecular and Anatomical Pathology Department, College of Medicine, University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria

cRadiotherapy, Radiobiology, Radiodiagnosis and Radiography Department, College of Medicine, University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria

dWest Cancer Centre and Research Institute, Memphis, TN, USA

eArrive Alive Diagnostics and Imaging Services Ltd, Lagos, Nigeria

fCorresponding Author: Adeoluwa Akeem Adeniji, Oncology and Radiotherapy Department, Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria

Manuscript submitted June 6, 2020, accepted July 16, 2020, published online August 10, 2020

Short title: Breast Cancer Among Nigerian Women

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/wjon1303

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Breast cancer in African women differs from the Caucasian. Understanding the profile of Nigerian women with breast cancer will help with preventive measures and treatment. This study focused on the clinico-pathological characteristics, with risk factors of breast cancer patients in Nigeria.

Methods: Newly diagnosed female patients with breast cancer were assessed over 12 months. Patients were reviewed using a predesigned proforma which focused on socio-demographic information, clinical information, risk factors and tumor biology.

Results: A total of 251 women were identified; their mean age was 46 years. More than half (62.5%) are premenopausal at presentation, 37.8% with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score of 0 and right side (50.2%) as the most common primary site of disease. Less than half of them (43.0%) are estrogen receptor (ER) positive, 27.9% are progesterone receptor (PR) positive, 43.8% and 47.4% are hormone receptor positive and triple negative, respectively. Most patients presented at the latter stage of the disease, stage III (66.9%) and stage IV (18.3%). Only 15.9% are well differentiated and almost all (92.8%) had invasive ductal histological type. Obesity (66.2%) and physical inactivity (41.9%) are the most common risk factors for the disease. A significant relationship was found between immunohistochemistry status and family history of breast cancer, tumor site, previous breast surgery, previous lump and alcohol intake.

Conclusion: Findings from this study showed that Nigerian breast cancer patients differ from their counterparts in the high human development index (H-HDI) countries in terms of the patients and disease characteristics. In view of this, prevention and treatment options should consider this uniqueness to ensure better outcome.

Keywords: Breast cancer; Subtypes; Tumor biology; Risk factors; Correlation; Nigeria

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Cancer is a major public health concern globally [1]. According to GLOBACAN, cancer is the single most important factor impacting life expectancy worldwide [2]. In women worldwide, breast cancer is the most common malignancy [3]. Every year, about 1 - 2 million new cases are diagnosed worldwide and this represents 10-12% of the female population [4]. In 2018 alone, there were 2.08 million new cases of breast cancer worldwide, and over 600,000 deaths, and this represents 11.6% new cases of cancer and 6.6% of all cancer-related deaths [2].

One of the indicators that reflect the development of each country, the status and their living conditions is the human development index (HDI). The HDI is defined as the average achievement of three factors, including life expectancy at birth, gross national income per capita, and mean and expected years of schooling. Low HDI level includes countries that are the least developed and the very high HDI level includes the most developed countries [5]. Although, low human development index countries (L-HDI) like Nigeria have a lower incidence of breast cancer when compared to high human development index (H-HDI) countries like the United States of America (USA), mortality rates are higher [6]. The incidence rate in the L-HDI countries is rising likely because of westernization and its lifestyle choices [7].

The high mortality rate is seen because of late stage presentation, misdiagnosis, and poor health seeking behavior, among other factors, of the African population in general. The screening rates is still low, ranging from 3.1% to 10.2%, for reasons ranging from cost, quality assurance and fear of radiation [8-11]. Studies have also shown that the genetic and histopathologic subtypes in African women are likely to be more aggressive than those seen in their Caucasian counterparts [12].

Worldwide, the treatment of breast cancer is now personalized, dependent on the patient, the stage and grade of disease, histological type, immunohistochemistry, drug preference, surgery and radiation impact and techniques for best outcomes. When the pathology, immunohistochemistry and tumor biology types are not factored into treatment modalities for these patients, coupled with late stage at presentation, poverty and lack of funding for treatment, there are worse outcomes for patients and this accounts for the high incidence of morbidity and mortality that is seen.

According to the Central Intelligence Agency fact book, there is 70% prevalence rate of poverty in Nigeria [13]. There is paucity of studies detailing biology or genetics of breast cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa, likely because of the difficulty involved in obtaining and processing tissue samples usually because of financial constraint [14], and due to the lack of laboratory facilities to carry out these investigations [15].

Currently, the management of Nigerian women with breast cancer is dependent on protocols imported from developed countries like the USA even though the patient population and disease profile may differ. Understanding the profile of Nigerian women with breast cancer helps to create prevention and treatment in a more personalized approach in management of the disease in Nigeria.

This study, therefore, focuses on exploring those characteristics in Nigerian patients, the differences seen when compared to their counterparts in H-HDI countries and hopes that these findings could impact prevention and management of breast cancer patients in Nigeria.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design

This is a non-interventional, prospective study among participants recruited from the Radiotherapy Unit of Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Idi-Araba, Nigeria. Participants were selected newly, histologically diagnosed with tumor staging (according to American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition) breast cancer patients who attended the outpatient clinics for treatment for the first time from July 2017 to July 2019. Participants were all females aged 18 years or more. Patients who were acutely ill (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score > 2) were excluded from the study. A structured interviewer-administered proforma was used to obtain required data from all study participants during the study period. The proforma collected data on socio-demographic and disease characteristics. Neutropenia and febrile neutropenia was graded using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.03. The CTCAE is a set of criteria for the standardized classification of adverse effects of drugs used in cancer therapy.

Measures

Study proforma

1) Socio-demographic and socioeconomic information

Participants were administered questionnaires aimed at gathering information about their age, marital status, level of education, occupation, partner’s occupation and economic status.

Patient’s occupation was categorized under three domains: unemployed (including student, housewife), minimally skilled (artisan, civil servant, trader) and skilled/professional (doctor, lawyer, accountant).

Patient’s marital status was defined into two categories: married or unmarried (divorced, separated, single and widowed).

2) Clinical information and risk factors

Participants were asked questions about their past medical history including: parity, first symptom, menopausal status and duration of illness. Risk factors like alcohol use, smoking, family history, use of contraceptive, breastfeeding and previous history of benign breast lesions were also elicited. Some clinical data were obtained by reviewing the patient’s hospital folder with a specific focus on cancer diagnosis, staging, surgery and ECOG performance of participants.

Body mass index (BMI) of each patient was calculated using the height and weight recorded in their medical case files at first presentation to the hospital. A BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more was defined as obesity and 25 kg/m2 or more was considered overweight.

Presence of comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus and peptic ulcer disease was recorded. Positive family history of breast cancer is defined as breast cancer both in first and second degree of patient’s family. Physical inactivity is measured by inability to move around, carry out day to day activities or at least 150 min of moderate intensity physical activity per week as recommended by the World Health Organization [16]. Early menarche is defined as first menstrual period in a female adolescent before the age of 12 years [17], while late first pregnancy is defined as above 35 years [18]. Previous lump is the presence of a benign lump that was removed before the onset of the breast malignancy.

3) Pathology and immunohistochemistry

Participants’ hospital folders were reviewed for data on pathologic staging of disease, pathologic information including histologic type, tumor grade and immunohistochemistry classification of disease. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2) is defined by immunohistochemistry only.

Data analysis

Data analysis was done using Statistical Package for Social Sciences software for Windows (version 21; SPSS, Chicago, IL). Univariate analyses were presented in the forms of tables as descriptive frequency distribution of the socio-demographic and immunohistochemistry of the patients. Correlation and association analyses were conducted using Chi-squared and analysis of variance (ANOVA), with a precision index of ≤ 0.05.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was sought from the ethics committee of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, and the study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was sought from every participant before undertaking to participate in the study.

| Results | ▴Top |

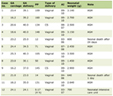

A total of 251 patients were seen as outpatients with histologically diagnosed breast cancer. The mean age of the patients studied was 46 years with a range of 18 - 76 years (Table 1). Majority (78.1%) live with a partner, 17.9% were unemployed and 39.8% attained tertiary level of education.

Click to view | Table 1. Characteristics of Breast Cancer Patients |

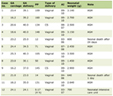

Table 2 summarizes the immunohistochemical status of the patients. Estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) positivity were 108 cases (73.0%) and 70 (27.9%), respectively. About one in every five (18.3%) had HER-2 positivity. Almost half (47.4%) have triple negative subtype.

Click to view | Table 2. Immunohistochemistry Distribution Among Breast Cancer Patients |

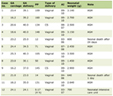

The majority of participants sampled suffered from right breast cancer (50.2%) (Table 3). The mean age at diagnosis and body mass index (BMI) at first presentation to the clinic were 45.6 years and 28.4 kg/m2. A total of 157 (62.5%) were premenopausal. A total of 75 (29.9%) had pre-existing comorbidities, while 41.8% have had breast surgery before and more than half (62.2%) presented with ECOG performance score ≥ 1. The most common primary site of tumor was the right.

Click to view | Table 3. Distribution of Clinical Characteristics by Tumor Subtype |

The most frequent histological type was invasive ductal with 233 cases (92.8%) (Table 4). Of these cancers, 40 (15.9%) were grade 1, 132 (52.6%) were grade 2 and 79 (31.5%) were grade 3. Stages I, II, III and IV were 0.8%, 13.9%, 66.9% and 18.3%, respectively with 17.5% having confirmed cases of organ metastasis and two cases (0.8%) did not have documented investigation of organ metastasis in their medical case files.

Click to view | Table 4. Distribution of Pathologic Characteristics by Tumor Subtype |

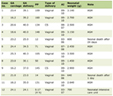

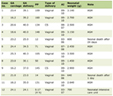

The most common risk factors identified with the participants were overweight/obesity (67.3%) and physical inactivity (58.2%). About 11.6% of patients studied had a family history of breast or any other type of cancer (Table 5).

Click to view | Table 5. Distribution of Risk Factors by Tumor Subtype |

A significant relationship was found between the HER-2 status and history of breast surgery (P= 0.016), tumor site (P= 0.010) (Table 3), family history of breast cancer (P= 0.004) and previous lump (P= 0.002) (Table 5). There was also a significant relationship between HR status and alcohol intake (P < 0.001) and family history of breast cancer (P= 0.009) (Table 5). The only significant relationship seen in triple negative subtype was with family history of breast cancer (P= 0.001) (Table 5). Immunohistochemistry status correlations with the age of the patients, age at diagnosis, menopausal status and the histologic type were not statistically significant.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

African-Americans (8%) in USA have more metastatic breast cancer when compared to other races (5-6%) and the same said for high-grade disease, larger tumor size and hormone receptor negativity in the blacks [19]. These are significantly increased among the blacks living in Africa [2, 6, 11].

This study clearly itemizes the socio-demographic, clinical, histological and immunohistochemistry characteristics of the Nigerian breast cancer patients in a hospital-based study. In this study, the mean age was 46 years with majority of women aged between 41 and 50 years, similar to the findings in previous studies in Nigeria but in contrast to western countries where most of the breast cancer patients are postmenopausal [5, 20]. Some studies have postulated a decrease in levels of circulating estrogen levels as responsible for the decreasing age of breast cancer patients worldwide [21, 22]. This finding emphasizes on the need for preventive, health education and screening programs not only targeted at the elderly because of the assumption that they are the prime age group at risk, while this might be true for western countries, and the pattern of disease presentation in Nigerian patients clearly highlights the need to begin screening for the disease before 40 years.

The previous studies conducted in Africa and Nigeria are largely hospital-based studies, and with small sample sizes making it difficult to predict associations between patients and risk factors. The finding of obesity and physical inactivity as the largest risk factors for breast cancer is new in the premenopausal group, although this was always true for many western countries mostly for postmenopausal women [23]. This finding is new in L-HDI countries like Nigeria and the predominance of the triple negative subset may account for this finding compared to the hormone receptor positive subset predominance in the western countries. In a similar study carried out in Nigerian women in 2008, early menarche and not breast feeding were the risk factors associated with increased risk of development of breast cancer. In this study, early menarche was only seen in 5.6% of breast cancer patients [24].

Family history is not a common risk factor in our patients as compared to their counterparts in H-HDI countries [25, 26]. The same is true for early menarche and nulliparity. Not surprisingly, the profile of risk in Nigerian cancer patients has evolved to mirror their Caucasian counterparts in the areas of obesity and physical inactivity [27, 28]. This finding helps to focus healthcare professionals during screening exercises not to rule out likely patients because of the absence of traditional risk factors like family history, early menarche or nulliparity.

In this study, like many other studies conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa, patients are seen in locally advanced and advanced stages of their diseases [29, 30]. This finding is not true for women in developed countries as patients tend to present at earlier stages [31]. Majority of the respondents were of moderate economic status, which suggests that funds may not be the reason for late stage presentation as seen in previous studies [32, 33]. Finding the reason why these patients presented late despite the fairly stable economic status is beyond the scope of this study and is open for further review. Perhaps the reason may be associated to the painless nature of their first symptom which may have affected their health seeking behavior.

In recent times, targeted therapies based on grade, histology and immunohistochemistry have resulted in better outcomes for patients [34, 35]. Globally, the invasive ductal carcinoma is the commonest histologic subtype of breast cancer [36]. This is true for breast cancer patients in this study representing 91% of the breast cancer patients seen.

Triple negative was the commonest subtype seen in these patients and differed from the less aggressive subtypes seen in Caucasian women [6, 25]. This subtype is associated with high rates of tumor invasion and metastases and is associated with a poorer prognosis [37]. This may explain the high mortality rates seen in the Nigerian breast cancer patients despite the comparatively lower incidence rates.

Conclusion

Nigerian breast cancer patient are likely to be premenopausal, obese or overweight, with no family history, of higher tumor grade, triple negative subtype, late stage and hormone receptor negative. These findings explain the high mortality rates seen in the Nigerian breast cancer patients, and can be modified or useful in targeted treatment to ensure a better outcome (Supplementary Material 1, www.wjon.org).

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Data of All Study Participants During the Study Period.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the entire staff of the department especially the medical record officers, nurses and the resident doctors.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding this work.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Adeoluwa Adeniji Akeem, Olayemi Olubunmi Dawodu, Muhammad Yaqub Habeebu, Ademola Oluwatosin Oyekan, Michael Martin, Bashir Mariam Adebola, Samuel Olalekan Keshinro. Financial support: Adeoluwa Adeniji Akeem, Olayemi Olubunmi Dawodu, Muhammad Yaqub Habeebu, Ademola Oluwatosin Oyekan, Bashir Mariam Adebola, Samuel Olalekan Keshinro. Administrative support: Adeoluwa Adeniji Akeem, Timilehin Gabriel Fagbenro, Bashir Mariam Adebola, Michael Martin. Provision of study materials or patients: Adeoluwa Adeniji Akeem, Muhammad Yaqub Habeebu, Ademola Oluwatosin Oyekan. Collection and assembly of data: Adeoluwa Adeniji Akeem, Ademola Oluwatosin Oyekan, Michael Martin, Bashir Mariam Adebola, Samuel Olalekan Keshinro. Data analysis and interpretation: Adeoluwa Adeniji Akeem, Timilehin Gabriel Fagbenro, Olayemi Olubunmi Dawodu, Muhammad Yaqub Habeebu. Manuscript writing: all authors. Final approval of manuscript: all authors. Accountable for all aspects of the work: all authors.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study have been deposited in OneDrive and can be accessed via the link at: https://cutt.ly/adeniji-breastcancer

| References | ▴Top |

- Ginsburg O, Bray F, Coleman MP, Vanderpuye V, Eniu A, Kotha SR, Sarker M, et al. The global burden of women's cancers: a grand challenge in global health. Lancet. 2017;389(10071):847-860.

doi - Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394-424.

doi pubmed - Ghoncheh M, Momenimovahed Z, Salehiniya H. Epidemiology, incidence and mortality of breast cancer in Asia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(S3):47-52.

doi pubmed - Shrivastava S, Singh N, Nigam AK, et al. Comparative study of hematological parameters along with effect of chemotherapy and radiotherapy in different stages of breast cancer. Int J Res Med Sci. 2017;5:311-315.

doi - Soheylizad M, Khazaei S, Jenabi E, Delpisheh A, Veisani Y. The relationship between human development index and its components with thyroid cancer incidence and mortality: using the decomposition approach. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2018;16(4):e65078.

doi pubmed - Igene H. Global health inequalities and breast cancer: an impending public health problem for developing countries. Breast J. 2008;14(5):428-434.

doi pubmed - Brinton LA, Figueroa JD, Awuah B, Yarney J, Wiafe S, Wood SN, Ansong D, et al. Breast cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities for prevention. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144(3):467-478.

doi pubmed - Akhigbe AO, Omuemu VO. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of breast cancer screening among female health workers in a Nigerian urban city. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:203.

doi pubmed - Lawal O, Murphy FJ, Hogg P, Irurhe N, Nightingale J. Mammography screening in Nigeria - A critical comparison to other countries. Radiography. 2015;21(4):348-351.

doi - Akinola R, Wright K, Osunfidiya O, Orogbemi O, Akinola O. Mammography and mammographic screening: are female patients at a teaching hospital in Lagos, Nigeria, aware of these procedures? Diagn Interv Radiol. 2011;17(2):125-129.

doi pubmed - MO O, Ayodele SO, Umar AS. Breast cancer and mammography: Current knowledge, attitudes and practices of female health workers in a tertiary health institution in Northern Nigeria. Screening. 2012;16:17.

doi - Agboola AJ, Musa AA, Wanangwa N, Abdel-Fatah T, Nolan CC, Ayoade BA, Oyebadejo TY, et al. Molecular characteristics and prognostic features of breast cancer in Nigerian compared with UK women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;135(2):555-569.

doi pubmed - Factbook CI. The world factbook. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook. 2010. Accessed on January 2nd, 2020.

- Fregene A, Newman LA. Breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: how does it relate to breast cancer in African-American women? Cancer. 2005;103(8):1540-1550.

doi pubmed - Akarolo-Anthony SN, Ogundiran TO, Adebamowo CA. Emerging breast cancer epidemic: evidence from Africa. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(Suppl 4):S8.

doi pubmed - Fuzeki E, Banzer W. Physical activity recommendations for health and beyond in currently inactive populations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(5).

doi pubmed - Ibitoye M, Choi C, Tai H, Lee G, Sommer M. Early menarche: A systematic review of its effect on sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0178884.

doi pubmed - Lampinen R, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K, Kankkunen P. A review of pregnancy in women over 35 years of age. Open Nurs J. 2009;3:33-38.

doi pubmed - DeSantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM, Newman LA, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(6):438-451.

doi pubmed - Ntekim A, Nufu FT, Campbell OB. Breast cancer in young women in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2009;9(4):242-246.

- Henderson BE, Ross R, Bernstein L. Estrogens as a cause of human cancer: the Richard and Hinda Rosenthal Foundation award lecture. Cancer Res. 1988;48(2):246-253.

- Bray F, McCarron P, Parkin DM. The changing global patterns of female breast cancer incidence and mortality. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(6):229-239.

doi pubmed - Wolin KY, Carson K, Colditz GA. Obesity and cancer. Oncologist. 2010;15(6):556-565.

doi pubmed - Huo D, Adebamowo CA, Ogundiran TO, Akang EE, Campbell O, Adenipekun A, Cummings S, et al. Parity and breastfeeding are protective against breast cancer in Nigerian women. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(5):992-996.

doi pubmed - Adesunkanmi AR, Lawal OO, Adelusola KA, Durosimi MA. The severity, outcome and challenges of breast cancer in Nigeria. Breast. 2006;15(3):399-409.

doi pubmed - Adebamowo CA, Adekunle OO. Case-controlled study of the epidemiological risk factors for breast cancer in Nigeria. Br J Surg. 1999;86(5):665-668.

doi pubmed - Porter P. "Westernizing" women's risks? Breast cancer in lower-income countries. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(3):213-216.

doi pubmed - McPherson K, Steel CM, Dixon JM. ABC of breast diseases. Breast cancer-epidemiology, risk factors, and genetics. BMJ. 2000;321(7261):624-628.

doi pubmed - Awofeso O, Roberts AA, Salako O, Balogun L, Okediji P. Prevalence and pattern of late-stage presentation in women with breast and cervical cancers in Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2018;59(6):74-79.

doi pubmed - Jedy-Agba E, McCormack V, Adebamowo C, Dos-Santos-Silva I. Stage at diagnosis of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(12):e923-e935.

doi - Vanderpuye V, Grover S, Hammad N, PoojaPrabhakar, Simonds H, Olopade F, Stefan DC. An update on the management of breast cancer in Africa. Infect Agent Cancer. 2017;12:13.

doi pubmed - Ibrahim NA, Oludara MA. Socio-demographic factors and reasons associated with delay in breast cancer presentation: a study in Nigerian women. Breast. 2012;21(3):416-418.

doi pubmed - Lannin DR, Mathews HF, Mitchell J, Swanson MS, Swanson FH, Edwards MS. Influence of socioeconomic and cultural factors on racial differences in late-stage presentation of breast cancer. JAMA. 1998;279(22):1801-1807.

doi pubmed - Sohn YM, Han K, Seo M. Immunohistochemical subtypes of breast cancer: correlation with clinicopathological and radiological factors. Iran J Radiol. 2016;13(4):e31386.

doi pubmed - Beral V, Bull D, Doll R, Peto R, Reeves G, Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast C. Breast cancer and abortion: collaborative reanalysis of data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 83?000 women with breast cancer from 16 countries. Lancet. 2004;363(9414):1007-1016.

doi - Li CI, Anderson BO, Daling JR, Moe RE. Trends in incidence rates of invasive lobular and ductal breast carcinoma. JAMA. 2003;289(11):1421-1424.

doi pubmed - Wu X, Baig A, Kasymjanova G, Kafi K, Holcroft C, Mekouar H, Carbonneau A, et al. Pattern of Local recurrence and distant metastasis in breast cancer by molecular subtype. Cureus. 2016;8(12):e924.

doi

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

World Journal of Oncology is published by Elmer Press Inc.