| World Journal of Oncology, ISSN 1920-4531 print, 1920-454X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, World J Oncol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.wjon.org |

Original Article

Volume 13, Number 6, December 2022, pages 350-358

Treatment Patterns Among Patients With Advanced Prostate Cancer in Brazil: An Analysis of a Private Healthcare System Database

Mariane S. Fontesa, Fabio A. Schutzb, Murilo de Almeida Luzc, Giovanni Bomfimd, Luciana Tarbes Mattana Saturninod, Sarah Carolina Goncalvesd, Roberto Solerd, e

aUro-oncologia, Grupo Oncoclinicas, Rio de Janeiro 22410-003, Brazil

bMedical Oncology, Beneficencia Portuguesa de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo 01323-001, Brazil

cHospital Erasto Gaertner, Curitiba 81520-060, Brazil

dMedical Affairs, Astellas Pharma Brazil, Sao Paulo - SP 04583-110, Brazil

eCorresponding Author: Roberto Soler, Medical Affairs, Astellas Pharma Brazil, Sao Paulo - SP 04583-110, Brazil

Manuscript submitted July 8, 2022, accepted September 1, 2022, published online December 1, 2022

Short title: Treatment of Prostate Cancer in Brazil

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/wjon1476

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: With the ongoing expansion of life-prolonging therapies approved to treat advanced prostate cancer, there is currently an unmet need to better understand real-world treatment patterns and identify optimal treatment sequencing for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).

Methods: In this retrospective, observational cohort analysis, patients with confirmed mCRPC were identified in the Auditron claims database and used to describe mCRPC treatment patterns and trends in the Brazilian private healthcare system from 2014 to 2019. Demographics and clinical characteristics, prostate cancer stage at diagnosis, and type and number of treatment lines were evaluated. The primary endpoint was identification of the drugs used in first-line therapies in mCRPC, and the secondary endpoint included a description of sequential lines of therapy (second and third lines) in mCRPC.

Results: A total of 168 electronic patient records were reviewed. Docetaxel was the most frequently used first-line treatment (35.7%), followed by abiraterone (33.3%) and enzalutamide (13.1%). Docetaxel, abiraterone, and enzalutamide also accounted for 34.6%, 28.0%, and 15.0%, respectively, of second-line therapies. In third-line therapies, cabazitaxel (26.1%), enzalutamide (23.9%), docetaxel (15.2%), and abiraterone (15.2%) were most commonly prescribed. Irrespective of stage at diagnosis, treatment patterns were similar once the disease progressed to the metastatic castration-resistance stage.

Conclusions: Docetaxel was the most frequently utilized therapy for mCRPC treatment, followed by abiraterone and enzalutamide. Although the current analyses provide real-world insights into treatment patterns for patients with mCRPC in Brazil, additional real-world data are needed to further validate and expand on these findings.

Keywords: Cancers; Real-world data; Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; Treatment patterns

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Prostate cancer was the second most frequently diagnosed cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer death among men worldwide in 2020 [1]. In Brazil, it is the most prevalent cancer among men, accounting for 29.2% of all cancers in this population and placing a considerable burden on the Brazilian healthcare system [2].

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is the standard treatment for the initial management of advanced prostate cancer; median ADT response is 18 - 24 months, while 10% of men have primary ADT resistance [3]. Although most patients initially respond to ADT, the development of castration-resistant disease is inevitable. Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) is lethal, with most patients surviving for approximately 3 years [4-8].

Until 2010, ADT plus docetaxel was the preferred drug combination as first-line treatment for mCRPC [4, 9-11]. Since then, there has been a shift in the treatment landscape following regulatory agency approval of several life-prolonging therapies (including cabazitaxel, abiraterone, enzalutamide, radium-223, and lutetium-177) [12-17]. More recently, the use of cabazitaxel as a second-line treatment has been decreasing while the use of novel hormonal therapies (NHTs) (i.e., abiraterone and enzalutamide) has been increasing [18]. With the increased availability of life-prolonging therapies and limited evidence on optimal drug sequencing, it is important to understand real-world treatment patterns to better leverage therapeutic advances and improve treatment outcomes in advanced prostate cancer.

Clinical trials have provided convincing evidence on the efficacy and safety of novel drugs, but given the strict eligibility criteria of clinical trials, the patient population included in them may not represent the spectrum of patients with prostate cancer who will receive treatment in the real-world setting. In particular, low-income patients, certain ethnic minorities, patients with comorbidities, and the elderly may be underrepresented [19]. Real-world data can be used to validate the findings of clinical trials, as well as to identify optimal patterns of care and the limitations associated with the use of novel therapies. Such information can help guide regulatory decisions, establish management guidelines, and improve clinical care.

Real-world data on mCRPC treatment patterns in Brazil are limited. A retrospective study performed in a public tertiary center in Sao Paulo from 2008 to 2013 evaluated the evolving treatment patterns after the approval of novel cancer agents. Exactly 197 patients with mCRPC and a Karnofsky performance status of ≥ 60% were included and 70% of them received docetaxel as a first-line therapy [20]; however, this study did not assess the subsequent lines of therapy after the failure of first-line treatment.

The healthcare system in Brazil is divided between private and public care. New therapies are generally incorporated into the private reimbursement listing after private health technology assessment (HTA) approval. New therapies are generally not incorporated as readily into the public health system, however, even though there is an established HTA approval process [21]. Therefore, access to new therapies is not readily available in the Brazilian public healthcare system and incorporation of novel technology can take years. In comparison, the private healthcare sector has the autonomy to establish treatment guidelines, so there is a broader access to novel drugs, although information on treatment patterns and sequencing is limited. Thus, there is an unmet need for real-world data to describe treatment patterns and sequencing in Brazil, which will help guide future studies, clinical practice, and local management guidelines.

This retrospective cohort study used the Auditron claims database to investigate real-world treatment patterns in patients with advanced prostate cancer in the Brazilian private healthcare system.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design

This was a retrospective, observational cohort study that reviewed data on the administrative claims from the Auditron database - a large, audited, Kantar-insured, private healthcare database in Brazil. The database contains data on chemotherapy and other systemic therapies from healthcare insurances representing 6% of the Brazilian oncology healthcare market and anonymized information on diagnosis, histology, staging, chemotherapy, systemic regimens, treatment duration, doses, cycles, and epidemiology. Data registered in Auditron are analyzed for consistency during quality-control checks performed by a team of clinical oncologists at Kantar. Queries are addressed through appropriate follow-up with the healthcare insurance companies. All analyses were reviewed by the medical intelligence director and the clinical research director at Kantar.

Patient population

Patients from the Auditron claims database were identified between January 1, 2014 and September 30, 2019; their data were selected for analysis if they were male with a prostate cancer diagnosis as determined by the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, of C61 and were undergoing ADT with documented evidence of castration resistance and clinical metastasis. Castration resistance was determined by an increase of ≥ 25% in prostate-specific antigen levels and an absolute increase of ≥ 2 ng/mL from the nadir while on ADT, despite castrate levels of testosterone [22]. A confirmatory prostate-specific antigen obtained ≥ 3 weeks later while on ADT was used to confirm progression. Conventional imaging (computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and bone scan) was used for diagnostic purposes.

Patients were also required to have had at least a 180-day interval between ADT initiation and their first clinical metastasis or progression of metastasis and/or initiation of treatment for mCRPC. ADT was defined as previous bilateral orchiectomy or use of at least one of the following drugs: leuprorelin, goserelin, triptorelin, histrelin, buserelin, and degarelix. Patients with a claim for at least one mCRPC treatment (abiraterone, enzalutamide, first-generation anti-androgen (bicalutamide or flutamide), docetaxel, cabazitaxel, or radium-223) on or after the onset date of castration resistance were included; those with a claim before the diagnosis of mCRPC were also included in the study, provided there was another claim for one of these drugs after the diagnosis of mCRPC.

Patients were excluded if there was an incomplete treatment description, defined as having no information on first-line treatment for mCRPC within the database or patients diagnosed with mCRPC more than 90 days before the first information on treatment.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was to identify the most frequently used first-line therapy for patients with mCRPC in the Brazilian private healthcare system. Secondary endpoints included the description of treatment sequencing patterns in the second- and third-line settings, and stratification of first-line therapy according to drug class.

First-line treatment was defined as the first systemic therapy registered in the database after mCRPC diagnosis based on a specific database field for previous treatments or whose claim was registered within the first 28 days (one cycle) after mCRPC diagnosis. If another therapeutic agent was added within 59 days of initiation of first-line treatment, this was defined as first-line combination therapy. Second-line treatment was defined as: 1) addition of a new agent after ≥ 60 days of initiation of first-line treatment, 2) switch to a new agent/regimen after ≥ 60 days of the index date (if there was a switch to a new treatment within the first 59 days of initiation of first-line treatment, this new regimen was considered part of first-line therapy), or 3) treatment (agent/regimen) restarted after a > 90-day therapy gap. Third-line treatment followed this same definition with respect to second-line treatment.

Statistical analyses

Standard descriptive analyses were used to describe baseline characteristics associated with the treatment of patients with mCRPC. All statistics were descriptive; continuous variables are described using mean, standard deviation, median, and minimum/maximum values. No data imputation was performed for missing values.

The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the responsible institution on human subjects as well as with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

| Results | ▴Top |

Study population

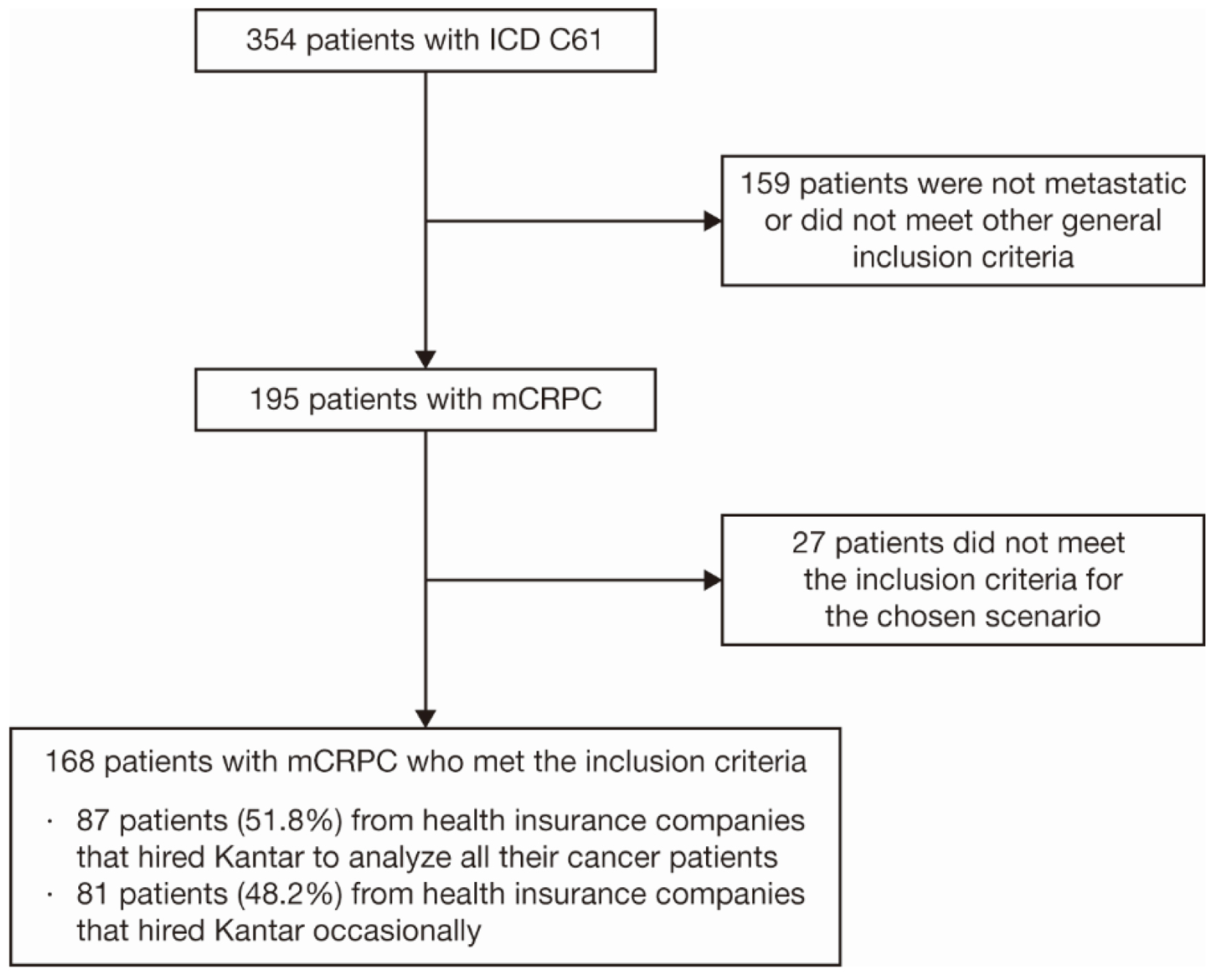

Between January 1, 2014 and September 30, 2019, 354 patients with a diagnosis of prostate cancer were identified. Of these patients, 195 had mCRPC and 168 met all inclusion criteria for this analysis (Fig. 1). Fifty-two percent of the data were from health insurance companies that hired Kantar to audit their patient data, while the other 48% of the data were from companies that hired Kantar occasionally. A sensitivity analysis was performed to compare the baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and first-line treatment (primary endpoint) between these two patient populations, and the results were similar (data not shown). The larger population (168 patients) was therefore considered for all analyses.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Patient selection criteria. Twenty-seven patients fell into the exclusion criteria: incomplete treatment, defined as having no information on first-line treatment for mCRPC within the database, or patients whose mCRPC diagnosis was made more than 90 days before the first information on treatment. ICD: International Classification of Diseases; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. |

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

The median age of patients at prostate cancer diagnosis and at the start of ADT was 66 and 68 years, respectively, while the median age at mCRPC diagnosis was 71 years. Most patients (39.9%) lived in the southeast region of Brazil. Of the patients with a known histology, 100% had adenocarcinoma and the remaining 0.6% (one patient) had an unknown histology (Table 1). Bone was the most commonly affected site of metastasis (97.6%), followed by lymph nodes (25.0%).

Click to view | Table 1. Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics |

Treatment patterns

The most common treatment in first-line therapy for mCRPC was docetaxel (35.7%), followed by abiraterone (33.3%) (Table 2). ADT monotherapy, followed by ADT plus a first-generation anti-androgen (bicalutamide or flutamide), was the most common treatment received before mCRPC diagnosis for all patients, at 50.9% and 32.3%, respectively (Table 3).

Click to view | Table 2. First-Line Treatment and Cycle Characteristics in Patients With mCRPC |

Click to view | Table 3. Treatment Received Before mCRPC Diagnosis (n = 167) |

Among patients who received second-line therapy, docetaxel (34.6%) was the most commonly used, followed by abiraterone (28.0%) and enzalutamide (15.0%). For third-line therapy, the most commonly used drugs were cabazitaxel (26.1%), enzalutamide (23.9%), docetaxel (15.2%), and abiraterone (15.2%).

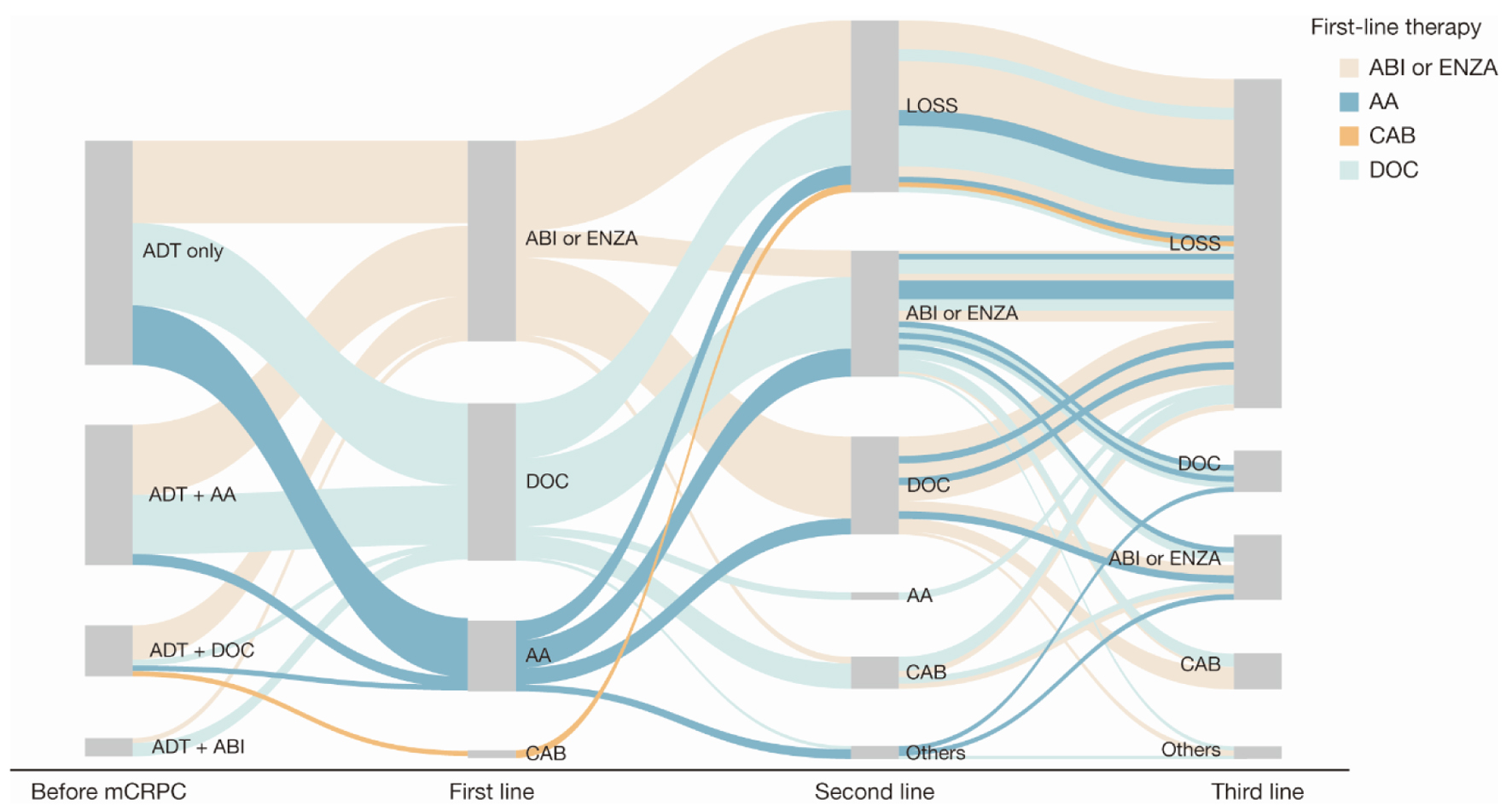

First-line therapy received for mCRPC treatment was evaluated according to the treatment received immediately before mCRPC diagnosis (Fig. 2, Table 4, and Supplementary Material 1, www.wjon.org). A total of 56.3% of patients who had received ADT plus a first-generation anti-androgen (bicalutamide or flutamide) before mCRPC diagnosis received either abiraterone or enzalutamide as first-line treatment. A total of 77.8% of patients who had received docetaxel for hormone-sensitive prostate cancer received abiraterone or enzalutamide upon progression as first-line therapy for mCRPC treatment. Seventy-eight patients received abiraterone or enzalutamide as first-line treatment for mCRPC. Among these patients, 10 also received abiraterone or enzalutamide as second-line treatment (Supplementary Material 1, www.wjon.org).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Sankey diagram of treatment pattern of patients with mCRPC (n = 168). AA: first-generation anti-androgen (bicalutamide or flutamide); ABI: abiraterone; ADT: androgen deprivation therapy; CAB: cabazitaxel; DOC: docetaxel; ENZA: enzalutamide; LOSS: information lost in tracking; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. |

Click to view | Table 4. First-Line Treatment for mCRPC According to Treatment Received Immediately Before mCRPC Diagnosis |

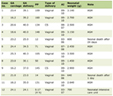

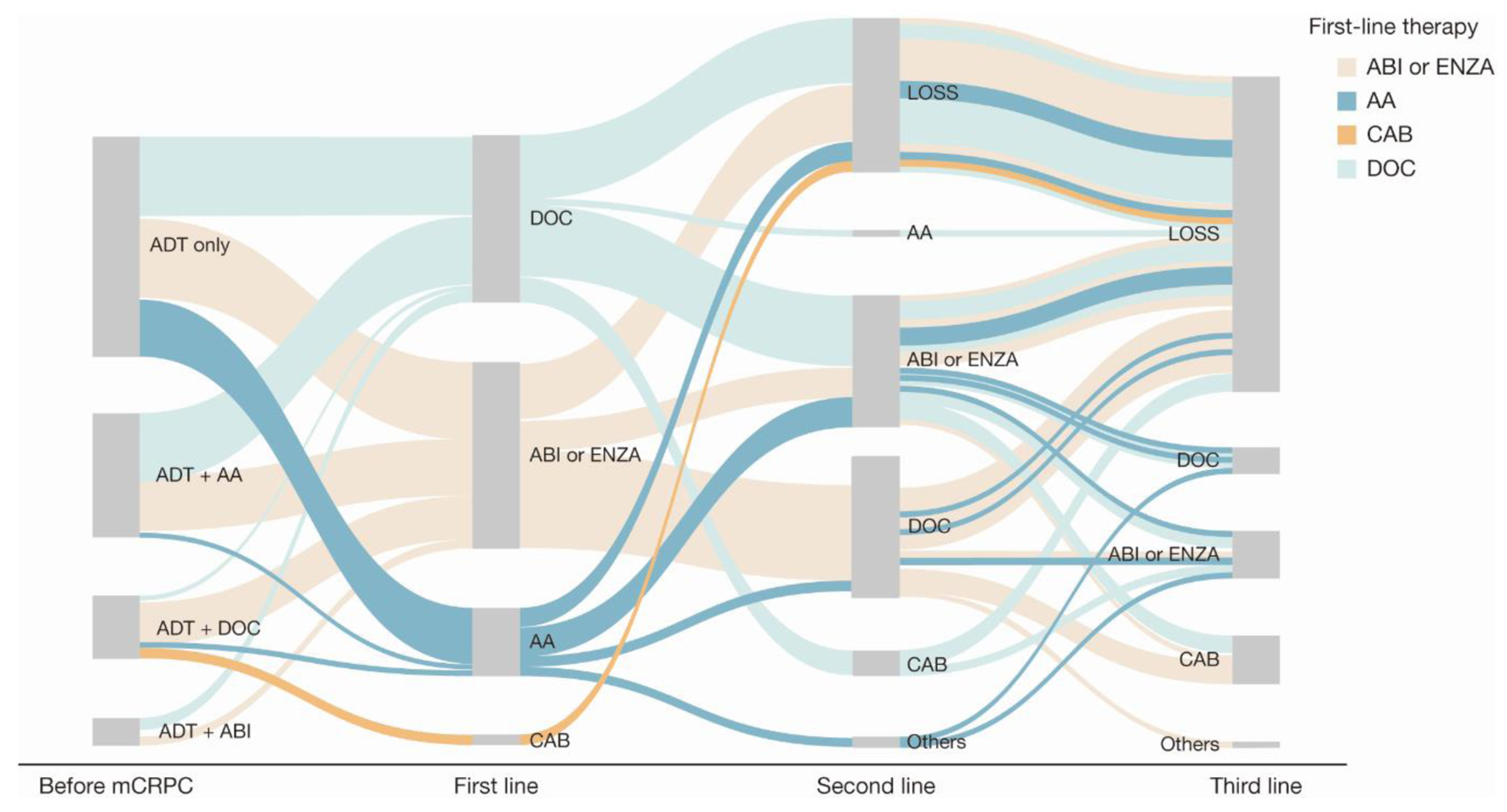

Treatment patterns among patients who were metastatic before their mCRPC diagnosis (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Material 2, www.wjon.org) were comparable with those of patients who were nonmetastatic before their mCRPC diagnosis (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Material 3, www.wjon.org).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Sankey diagram of treatment pattern of patients who were metastatic before mCRPC diagnosis (n = 122). AA: first-generation anti-androgen (bicalutamide or flutamide); ABI: abiraterone; ADT: androgen deprivation therapy; CAB: cabazitaxel; DOC: docetaxel; ENZA: enzalutamide; LOSS: information lost in tracking; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Sankey diagram of treatment pattern of patients who were non-metastatic before mCRPC diagnosis (n = 45). AA: first-generation anti-androgen (bicalutamide or flutamide); ABI: abiraterone; ADT: androgen deprivation therapy; CAB: cabazitaxel; DOC: docetaxel; ENZA: enzalutamide; LOSS: information lost in tracking; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This retrospective analysis of the Auditron claims database provides real-world insights into the treatment patterns of patients with advanced prostate cancer treated in the private healthcare system in Brazil, particularly in the southeast region. Docetaxel was the most commonly prescribed first-line treatment, while NHTs were increasingly administered later in treatment sequencing (second and third lines). ADT monotherapy was the most common treatment patients received before mCRPC diagnosis, even for those with metastatic disease, followed by ADT plus a first-generation anti-androgen (bicalutamide or flutamide).

Treatment patterns identified in our analysis were comparable with those from another recently published Brazilian real-world retrospective study that reported that 70% of patients with mCRPC received docetaxel as the first-line therapy [20]. Although docetaxel was more frequently used, it was closely followed by abiraterone. The current data contrast with American reports, which show abiraterone and enzalutamide to be the most frequently used first- and second-line treatments, respectively [12, 23-25]. The differences observed in treatment options may be a consequence of the timing of drug approval by the Brazilian regulatory agency Agencia Nacional de Vigilancia Sanitaria (ANVISA) and the subsequent approval by the Brazilian private healthcare system regulatory agency Agencia Nacional de Saude Suplementar, responsible for determining the minimum mandatory reimbursement, consequently delaying the incorporation and availability of drugs.

Abiraterone approval preceded enzalutamide approval by 1 year, which could explain the higher use of abiraterone. ANVISA only recently approved enzalutamide for the treatment of metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer [26]. It is important to note that the recent approval of NHTs by the Brazilian regulatory agencies and the increasing use of these drugs in private healthcare practices will probably increase the disparities in treatment patterns between the private and public healthcare systems as the approvals by the public health system are deferred due to availability of resources. Currently, access to NHTs in the public healthcare system is limited.

Despite the mounting body of evidence supporting the superiority of adding another drug such as docetaxel and abiraterone (and enzalutamide and apalutamide later) to ADT for patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer, most patients with metastatic disease had received ADT monotherapy (50.8%) or ADT plus a first-generation anti-androgen (28.7%) before their mCRPC diagnosis. This finding mirrors the results of real-world treatment patterns found in the US health insurance database [27] and may be due to regulatory approvals, which currently do not include NHTs in the minimum mandatory reimbursement for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer.

A large, observational, real-world study of treatment patterns and outcomes with systemic therapy in men with metastatic prostate cancer in the United States also described the underutilization of NHTs and docetaxel for the treatment of metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer despite large, randomized trials showing significantly improved survival outcomes with these treatments [27]. In this study, most patients (54%) received only ADT as the first metastatic prostate cancer treatment after metastatic diagnosis; however, the study noted that although the use of NHTs is low in this setting, a gradual and encouraging increase in their use has been observed in the last 5 years.

Despite the lack of guidelines on optimal treatment sequencing for patients with mCRPC, there is some evidence from observational, real-world studies indicating a preferential use of abiraterone and enzalutamide as first-line therapy [2, 28]. Furthermore, at the 2019 Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference, an expert consensus reported that abiraterone and enzalutamide were the preferred first-line treatments for advanced prostate cancer, followed by a taxane in men with symptomatic mCRPC plus progressive disease as the best response to first-line abiraterone or enzalutamide [29]. However, some studies also indicated the possibility of cross-resistance between abiraterone and enzalutamide, thus affecting treatment decisions [30-32].

In the current study, a greater proportion of patients received an NHT (abiraterone or enzalutamide) as first-line treatment after chemotherapy than those who received abiraterone or enzalutamide after receiving another NHT (78% vs. 22%, respectively). Among those patients receiving docetaxel as a first-line treatment for mCRPC, 68% received an NHT and 26% received cabazitaxel as a second-line treatment. Among patients who received an NHT as the first-line treatment, followed by chemotherapy as the second-line treatment, similar proportions received either an NHT or cabazitaxel as the third-line treatment. The CARD trial (NCT02485691) comparing the efficacy of cabazitaxel with that of NHTs as a third-line treatment option for mCRPC showed the superiority of cabazitaxel in terms of increased overall survival (13.6 vs. 11.0 months). In addition, it confirmed the modest efficacy of NHTs in this context [33]. These results describe a trend of avoiding the use of multiple NHTs sequentially, with a preference for alternating NHTs with chemotherapy.

While this study using real-world patient-level data is an objective evaluation of advanced prostate cancer treatments in a cohort of patients in Brazil, it did have some limitations. First, due to the retrospective study design, loss of follow-up, early termination of treatment, change in treatment institution, and incomplete data were intrinsic limitations. Second, the study was conducted with data from an anonymized claims database, and therefore, only clinical information related to the claims was available. Third, since 168 patients primarily from the southeast region of Brazil were included in the analysis and only 6% of all private healthcare system insurance companies were represented in the analysis, subsequent studies that include a larger and more diverse patient population should be conducted to validate and confirm treatment patterns. Fourth, as the data were analyzed in a descriptive way using observations available, formal statistical comparisons could not be drawn, and no imputation for missing data was conducted.

Conclusions

The current analysis provides real-world insights into treatment patterns for patients with advanced prostate cancer in Brazil. Although docetaxel was the most frequently utilized therapy for mCRPC treatment, followed by abiraterone and enzalutamide, the treatment patterns identified here describe the relatively low use of ADT plus NHTs; therefore, it is possible that patients with mCRPC who could benefit from NHTs may be undertreated. Additional studies conducted in real-world settings evaluating larger patient populations are needed to track changes in treatment patterns and to provide information on how specific sequences of therapies affect clinical outcomes in mCRPC.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Treatment Pattern of Patients With mCRPC Before mCRPC Diagnosis to Third-Line Treatment for Total Population - Aggregated Data (n = 168)

Suppl 2. Treatment Pattern of Patients With mCRPC From mCRPC Diagnosis to Third-Line Treatment for the Population of Patients With Metastasis Before mCRPC Diagnosis - Aggregated Data (n = 122)

Suppl 3. Treatment Pattern of Patients With mCRPC Before mCRPC Diagnosis to Third-Line Treatment for the Population of Patients Who Were Not Metastatic Before mCRPC Diagnosis - Aggregated Data (n = 45)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kantar for its support in data collection from the Auditron database. Medical writing assistance was provided by Mashal Hussain, PhD, and editorial support was provided by Jane Beck, MA (Hons), from Complete HealthVizion IPG Health Medical Communications, funded by the study sponsors.

Financial Disclosure

This study was funded by Astellas Pharma Inc. and Pfizer Inc., the co-developers of enzalutamide. The authors received no compensation related to the development of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

MF has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaker bureaus, publication writing or educational events from Janssen, AstraZeneca, MSD, Bayer, Astellas, BMS, Amgen, Roche, Zodiac, and Ipsen; received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Janssen, Roche, MSD, BMS, Astellas, Merck, and AstraZeneca; and has participated in Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board sponsored by Janssen, and Roche. FS has received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Zodiac, Janssen, and Astellas; has participated in Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board sponsored by Janssen, MSD, AstraZeneca, Zodiac, BMS, Astellas, Bayer, and Ipsen; and has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations or speaker bureaus from Janssen, MSD, Zodiac, BMS, Astellas, Bayer, Ipsen, and AstraZeneca. MAL has received speaker and Advisory Board participation fees from Astellas, Janssen, Sanofi, ProScan, and Bayer; received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Janssen, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Bayer; and received research funding from Amgen, Ferring, AstraZeneca, ProScan, Janssen, Bayer, GSK, and Active Biotech. LTMS, GB, SCG, and RS are employees of Astellas Pharma Brazil.

Informed Consent

Informed consents were obtained.

Author Contributions

RS, SCG, GB, and LTMS contributed to the conception and design of the study and were involved in acquisition of study data. RS, SCG, GB, LTMS, MF, FS, and MAL contributed to the interpretation of the study data and writing or critically revising at every development stage. The authors take full responsibility for the scope, direction, and content of the manuscript and have approved the submitted manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

ADT: androgen deprivation therapy; ANVISA: Agencia Nacional de Vigilancia Sanitaria; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; NHT: novel hormonal therapy

| References | ▴Top |

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249.

doi pubmed - INCA. 2020. Available from: https://www.inca.gov.br/numeros-de-cancer.

- Mar N, Kalebasty AR, Uchio EM. Management of advanced prostate cancer in clinical practice: real-world answers to challenging dilemmas. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(12):783-789.

doi pubmed - Snoeks LL, Ogilvie AC, van Haarst EP, Siegert CE. New treatment options for patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Neth J Med. 2013;71(6):290-294.

- Doctor SM, Tsao CK, Godbold JH, Galsky MD, Oh WK. Is prostate cancer changing?: Evolving patterns of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(6):833-839.

doi pubmed - Caffo O, Maines F, Rizzo M, Kinspergher S, Veccia A. Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in very elderly patients: challenges and solutions. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:19-28.

doi pubmed - Chi KN, Kheoh T, Ryan CJ, Molina A, Bellmunt J, Vogelzang NJ, Rathkopf DE, et al. A prognostic index model for predicting overall survival in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with abiraterone acetate after docetaxel. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(3):454-460.

doi pubmed - Nakabayashi M, Hayes J, Taplin ME, Lefebvre P, Lafeuille MH, Pomerantz M, Sweeney C, et al. Clinical predictors of survival in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: evidence that Gleason score 6 cancer can evolve to lethal disease. Cancer. 2013;119(16):2990-2998.

doi pubmed - Danila DC, Morris MJ, de Bono JS, Ryan CJ, Denmeade SR, Smith MR, Taplin ME, et al. Phase II multicenter study of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone therapy in patients with docetaxel-treated castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(9):1496-1501.

doi pubmed - Tran C, Ouk S, Clegg NJ, Chen Y, Watson PA, Arora V, Wongvipat J, et al. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science. 2009;324(5928):787-790.

doi pubmed - Lorente D, Fizazi K, Sweeney C, de Bono JS. Optimal treatment sequence for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol Focus. 2016;2(5):488-498.

doi pubmed - Wen L, Valderrama A, Costantino ME, Simmons S. Real-world treatment patterns in patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2019;12(3):142-149.

doi pubmed - de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, Hansen S, Machiels JP, Kocak I, Gravis G, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1147-1154.

doi - de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, Fizazi K, North S, Chu L, Chi KN, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):1995-2005.

doi pubmed - Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, Taplin ME, Sternberg CN, Miller K, de Wit R, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(13):1187-1197.

doi pubmed - Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, Helle SI, O'Sullivan JM, Fossa SD, Chodacki A, et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(3):213-223.

doi pubmed - Sartor O, Fougere C, Essler M, Ezziddin S, Kramer G, Ellinger J, Nordquist L, et al. (177)Lu-prostate-specific membrane antigen ligand after (223)Ra treatment in men with bone-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: real-world clinical experience. J Nucl Med. 2022;63(3):410-414.

doi pubmed - Kim HS, Lee S, Kim JH. Real-world evidence versus randomized controlled trial: clinical research based on electronic medical records. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33(34):e213.

doi pubmed - Scher HI, Halabi S, Tannock I, Morris M, Sternberg CN, Carducci MA, Eisenberger MA, et al. Design and end points of clinical trials for patients with progressive prostate cancer and castrate levels of testosterone: recommendations of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(7):1148-1159.

doi pubmed - Maia MC, Pereira AAL, Lage LV, Fraile NM, Vaisberg VV, Kudo G, Barroso-Sousa R, et al. Efficacy and safety of docetaxel in elderly patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1-9.

doi - Lessa F, Ferraz MB. Health technology assessment: the process in Brazil. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2017;41:e25.

- Gul A, Garcia JA, Barata PC. Treatment of non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: focus on apalutamide. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:7253-7262.

doi pubmed - George DJ, Sartor O, Miller K, Saad F, Tombal B, Kalinovsky J, Jiao X, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in a real-world clinical practice setting in the United States. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2020;18(4):284-294.

doi pubmed - Wen L, Yao J, Valderrama A. Evaluation of treatment patterns and costs in patients with prostate cancer and bone metastases. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(3-b Suppl):S1-S11.

doi pubmed - Halwani AS, Rasmussen KM, Patil V, Li CC, Yong CM, Burningham Z, Gupta S, et al. Real-world practice patterns in veterans with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2020;38(1):1.e1-e10.

doi pubmed - Reis LO, Dal Col LSB, Sadi MV. National consensus on non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: more than just a snapshot. Int Braz J Urol. 2021;47(2):374-377.

doi pubmed - Swami U, Sinnott JA, Haaland B, Sayegh N, McFarland TR, Tripathi N, Maughan BL, et al. Treatment pattern and outcomes with systemic therapy in men with metastatic prostate cancer in the real-world patients in the United States. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(19):4951.

doi pubmed - Vasani D, Josephson DY, Carmichael C, Sartor O, Pal SK. Recent advances in the therapy of castration-resistant prostate cancer: the price of progress. Maturitas. 2011;70(2):194-196.

doi pubmed - Gillessen S, Attard G, Beer TM, Beltran H, Bjartell A, Bossi A, Briganti A, et al. Management of patients with advanced prostate cancer: report of the Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference 2019. Eur Urol. 2020;77(4):508-547.

doi pubmed - Zhang T, Dhawan MS, Healy P, George DJ, Harrison MR, Oldan J, Chin B, et al. Exploring the clinical benefit of docetaxel or enzalutamide after disease progression during abiraterone acetate and prednisone treatment in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2015;13(4):392-399.

doi pubmed - Matsubara N, Yamada Y, Tabata KI, Satoh T, Kamiya N, Suzuki H, Kawahara T, et al. Abiraterone followed by enzalutamide versus enzalutamide followed by abiraterone in chemotherapy-naive patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018;16(2):142-148.

doi pubmed - Miyake H, Hara T, Terakawa T, Ozono S, Fujisawa M. Comparative assessment of clinical outcomes between abiraterone acetate and enzalutamide in patients with docetaxel-naive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: experience in real-world clinical practice in Japan. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15(2):313-319.

doi pubmed - de Wit R, de Bono J, Sternberg CN, Fizazi K, Tombal B, Wulfing C, Kramer G, et al. Cabazitaxel versus abiraterone or enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(26):2506-2518.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

World Journal of Oncology is published by Elmer Press Inc.